THE DOCUMENTS:

• N.M. Foundation For Open Government’s notice of violation

• Doña Ana County’s response

ARTICLE SUMMARY: Doña Ana County commissioners violated the state’s Open Meetings Act by approving drafts of agreements with the developers of Project Jupiter and giving one commissioner the authority to finalize those documents in private, the N.M. Foundation for Open Government says. I agree. Here’s why it matters, and what comes next.

This article is a long read. If you’d rather listen, click the play button in the audio player:

FULL ARTICLE: Let’s start with the bottom line: Boards that oversee local government agencies in New Mexico must make all decisions in public so you can watch.

There are no exceptions. Not doing their work in public cuts you out of the decision-making process and violates the N.M. Open Meetings Act.

That’s why it was illegal for the Doña Ana County Board of Commissioners to approve draft agreements with the developers of Project Jupiter and give Commission Chair Christopher Schaljo-Hernandez the authority to negotiate final details in private, according to the N.M. Foundation for Open Government.

“The fact that we don’t know what they changed, that’s literally the problem,” said Christine Barber, FOG’s executive director. “…They are breaking the law.”

After investigating this situation and considering the arguments on both sides, I agree.

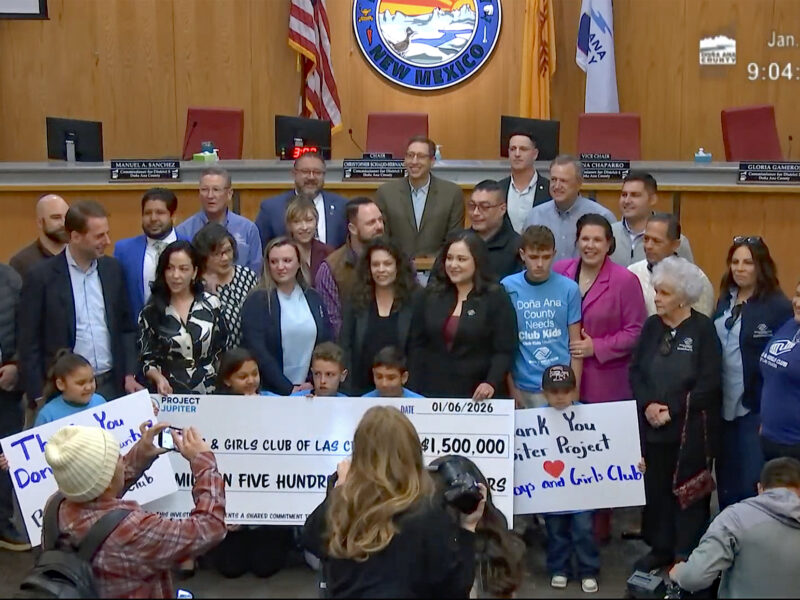

At their Sept. 19 meeting, commissioners left it to Schaljo-Hernandez to put the final touches on about a dozen legal agreements, including leases. Those documents are part of a complex bond deal that gives the developers a 30-year exemption from paying property taxes in exchange for promises that include annual $12 million payments to the county.

Commissioners voted 4-1 to advance drafts that day.

Schaljo-Hernandez has told me he would ensure that what’s finalized matches what commissioners intended. But more than 11 weeks later, the public still hasn’t seen final agreements and has no way to know if that’s true.

In the meantime, construction at Project Jupiter’s build site in Santa Teresa is already underway.

That’s the problem. If we find out Schaljo-Hernandez didn’t keep his promise to the public, it may be too late to do anything about it. And even if Schaljo-Hernandez honors his pledge, commissioners have set a precedent of allowing backroom dealing that creates the potential for abuse later.

It must be stopped now.

Sloppy and confusing

The Open Meetings Act makes it state’s policy that “all persons are entitled to the greatest possible information regarding the affairs of government and the official acts of those officers and employees who represent them.”

Rather than being informative, the county’s process of approving financial incentives to entice the developers to build the campus of data centers in Santa Teresa has been, at best, sloppy and confusing. On the day of the vote, the bond agreements were missing details. Documents were labeled as drafts; some included blank pages.

Commissioner Susana Chaparro voted against the tax incentives, saying approving drafts would be inappropriate. The night before the meeting, I called for commissioners to postpone the vote.

But with the developers threatening to walk away from the deal if the county delayed approval, the other four commissioners voted to move ahead.

County residents did not have the information on Sept. 19 that they needed to understand what their commissioners were voting to approve, let alone make their voices heard in a way that could have improved the proposals.

That contributed to the lengthy outpouring of anger during public input at the Sept. 19 meeting.

It’s no secret that I’ve been upset ever since. I place the highest value on government transparency, which is a core building block of a democracy.

If the county process hadn’t been so messy I would be more enthusiastic about Project Jupiter. We need the jobs and its pledged water use is much less than that of many other data centers — though its stated pollution estimates are ridiculous.

Pattern of delays

Regardless, with construction already underway, a determination of whether the county complied with state transparency law won’t likely kill the project.

What’s at stake are the tax breaks. It seems unlikely Project Jupiter’s developers will go elsewhere even if they lose those incentives.

After weeks of negotiating final details and dealing with legal challenges, Schaljo-Hernandez told me a week ago, on Dec. 1, that he has signed final documents related to the issuance of $165 billion in industrial revenue bonds. Those transactions are finalized.

He said all of those documents — leases and other legally binding agreements — would be online for the public to see as soon as that afternoon.

“We’re excited for everyone to see all the agreements in black and white — signed, sealed and delivered,” Schaljo-Hernandez said.

Those documents are still not online as of publication of this article a week later. That continues the pattern of delays in releasing information to the public.

Finalizing policy in secret

Meanwhile, FOG sent a formal notice of violation to the county on Nov. 14 alleging that commissioners violated the Open Meetings Act at the Sept. 19 meeting.

Even after approval, every page of the official, signed-and-stamped copy of the ordinance authorizing the property tax exemption, which I obtained from the County Clerk’s Office through a public records request, has a “draft” watermark on it.

The commission’s “failure to deliberate on and pass” the final version of the ordinance at a public meeting means it is invalid, FOG’s letter states. The letter asserts that a second ordinance authorizing a partial exemption from paying gross receipts tax is invalid for the same reason.

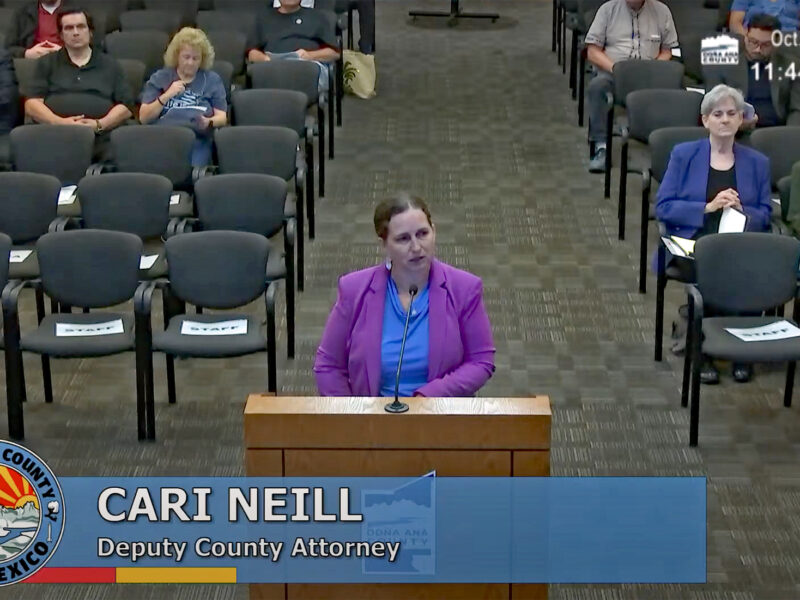

Interim County Attorney Cari Neill responded Tuesday, stating in her letter that commissioners approved final versions of their ordinances at the September meeting. Even if one had a draft watermark, the ordinances haven’t changed.

It’s the documents the bond ordinances authorized that day — including lease agreements — that were still in draft form, Neill wrote.

Again, the bottom line: Schaljo-Hernandez finalized public policy outside of public view. “I don’t think the distinction between the ordinance or the attachments is relevant,” FOG Legal Director Amanda Lavin told me.

Commissioners left big questions in the hands of Schaljo-Hernandez. How many gallons of water will the county let Project Jupiter use each day? Will it be required to build a closed-loop system for cooling electronics to reduce water use? Will donations the developers pledged for various community projects come to fruition? And will any of those things end up in legally binding documents that are actually enforceable?

The Open Meetings Act requires the resolution of questions like these in public.

Inexcusable

In her letter, Neill defended the county in part by asserting that it had provided the public with “as much information as possible at every step,” thus complying with the Open Meetings Act’s statement that the public is entitled to “the greatest possible information.”

I disagree, wholeheartedly. The fact that the county has finalized the bond agreements but still not released them to the public proves the point. Asking Chaparro and other commissioners to approve drafts with details to be filled in later does, too.

Every step has gone that way.

The New York Times has noted the lack of clarity about terms of the deal by mentioning its own inability to obtain legal agreements in a timely manner.

“A week after this reporter asked for a copy of the contract, an email arrived from the Doña Ana County records office deeming the request ‘excessively burdensome,’” the newspaper wrote in an article about Project Jupiter published Sunday. “Expect a response by mid-January, the email said.”

There’s nothing burdensome about a request for these legal agreements. The county needs to do no research and digging to collect them. They’re literally sitting on someone’s desk — or desktop — waiting to be put on the county’s website.

The fact that many of these agreements aren’t yet online is inexcusable. So is the delay in releasing them to The Times and others.

What now?

We need action to enforce the Open Meetings Act and teach the county what compliance looks like. Commissioners need to correct their violations of the transparency law.

Historically, that means redoing votes. Such public meetings usually include explanations of the violations and hopefully apologies, in addition to new opportunities for the public to be heard.

FOG’s letter doesn’t force the county to take action. But it does give the organization standing to sue if commissioners fail to correct their violations.

Lavin said a lawsuit is possible. So is a complaint to the N.M. Department of Justice, which would trigger a legal review and possible action by the state attorney general.

Lauren Rodriguez, the DOJ’s chief of staff, confirmed that at least two citizens have already filed Open Meetings Act complaints related to the Commission’s Sept. 19 votes. Those complaints “will now move through our standard process, which includes assignment to an attorney for review,” she said.

County residents understand the problem. They’re asking the right questions.

“Can the Commission really approve an agreement with provisions ‘to be announced?’” asked Jo Ann Bingel of Las Cruces in one of the complaints to the DOJ. “And, doesn’t the public have a right to know what exactly the Commission is approving?”

Believing a bluff

The county is also battling two lawsuits that challenge the tax breaks on the grounds that it didn’t follow other required procedures before approval. But construction is charging ahead.

Crews have leveled the massive build site, as aerial photos published by The Times show. The county has issued a permit to level the property (view the application and the plans). The state has permitted construction of a road for temporary access (here and here).

The developers have filed applications for permits to build two microgrids powered by natural gas that will supply electricity for the data centers (view those here and here).

The microgrids will pump a nearly unbelievable amount of greenhouse gas into the air — potentially more than twice what’s emitted by the state’s two largest cities combined, Source New Mexico reported.

The state regulates that aspect of Project Jupiter, and pollution numbers were not something county commissioners required disclosure on before voting to approve tax breaks in September. That’s another consequence of the rush.

While dangling the promises of jobs and payments to the county of $12 million a year, the developers threatened to go elsewhere if commissioners didn’t approve their tax breaks on Sept. 19. “This is a generational opportunity. It is here today,” Lanham Napier, the chairman of BorderPlex Digital Assets, one of the companies involved, told commissioners that day.

“A vote to delay it is basically a vote no,” Napier said.

That demand precipitated the county’s frenzied and problematic approval process.

I call bullshit. With the developers not waiting to see whether their coveted tax breaks materialized before charging ahead, it seems likely they were bluffing.

Scorched earth

The governor fast-tracked this deal when she announced it alongside Napier in February. Meanwhile, BorderPlex Digital’s lobbyists were sneaking legislation to allow massive microgrids onto the governor’s desk for her signature.

By the time Project Jupiter came to Doña Ana County for approval of tax breaks, the pressure to close the deal was immense.

County officials appeased developers and state officials who demanded speed, non-disclosure agreements and, ultimately, tax incentives.

It’s in moments like these that the Open Meetings Act is critical. It prohibits government agencies from acting in secret alongside outside interests. It’s designed to pull officials back toward the people they were elected to represent and ground them in those relationships.

I don’t doubt that the four commissioners who voted for the tax breaks believe they were doing the right thing for their constituents. But they did it without going through the public process required by state law, and they scorched earth with many county residents. That wound will not easily heal.

Violating the Open Meetings Act is a misdemeanor criminal offense that’s enforceable by a district attorney or the state attorney general. That’s rarely done. Five former members of the Las Cruces school board carry the notorious distinction of being the only people in the state’s history convicted of violating the law.

While the state DOJ prefers education to improve compliance over enforcement in court, the criminal option is always on the table.

So is a civil lawsuit from FOG, the DOJ or someone else that could undo the tax breaks commissioners approved. That would put in jeopardy the county’s work to negotiate protections and benefits, but it would almost certainly result in lots more money coming to the county and school districts from property taxes.

Regardless, I hope it’s becoming clear to county commissioners that this isn’t the appropriate way to operate.

The Open Meetings Act exists for good reason. It isn’t difficult to understand and it’s not negotiable. Whatever transpires next with the state DOJ or in court was avoidable.

Disclosure: My spouse, state Rep. Sarah Silva, is a supporter of Project Jupiter.

The bottom line is DAC does not have the expertise, either on the BOCC, or in county management to act responsibly in this matter. They are currently flummoxed by far less complicated matters. Project Jupiter is not in our league.

Thanks for weighing in, sheriff.

Well done. I suspect the NYT’s David Segal’s article’s final paragraph captures the dynamic of it all: “You promise a great thing, you sell the story hard, you get people to buy in before the thing actually exists, he said (Kedrosky). “That’s how the game is played in this ‘new industrial revolution.'” The stench of limitless sums of money in this so-called “revolution” is corrupting everything in its way. I don’t think it’s hyperbole to say that we are all in existential peril and must resist.

Thanks for highlighting that!

Today, The Guardian reported that more than 200 environmental groups called for a halt to these water guzzling, cimate wrecking datacenters. It is unfathomable that DAC Commissioners approved such a project for Dona Ana County. It doesn’t matter how many jobs are created if the planet is rendered uninhabitable.

Thanks for weighing in! The climate data for Project Jupiter is… wow.

Another thing that isn’t being taken into account is the combined impact of Project Jupiter and the Meta data center being built in El Paso. In other words, the negative impacts to this region will be much worse than currently projected.

Yes, that Meta data center, which is right on the NM border south of Chaparral, is allowed to use more than 10 times the water that Project Jupiter agreed to!

In the meeting that was held in the Farm and Ranch Museum, the developers clearly and repeatably stated that the facility would provide “100% its’ own renewable energy, catch and recycle all the water needed for cooling, and comply with all of state and federal environmental legal requirements”. Before they are given final approval, they should be legally bound to their promises in such a way that if they don’t comply, development and/or operation of the facility will be for fitted and stopped!

The current legal requirement is that they be renewable by 2045. Also, for an update on the agreements, out my newest article on this topic: https://haussamen.com/2025/12/18/final-project-jupiter-agreements-grew-exponentially/