ARTICLE SUMMARY: There are dozens of license plate readers around Las Cruces and Doña Ana County. They’re owned by a private company and leased to law enforcement agencies. They play an increasing role in police work but have privacy advocates sounding the alarm.

Concerns include the possibility that data could be shared with the federal government for immigration enforcement or used by police in states where abortion is illegal to track women. The Las Cruces City Council and N.M. Legislature are currently considering ways to regulate the technology and protect residents.

This article is a long read. If you’d rather listen, click the play button in the audio player. Also, you’ll find links to government documents that informed this reporting at the end of the article.

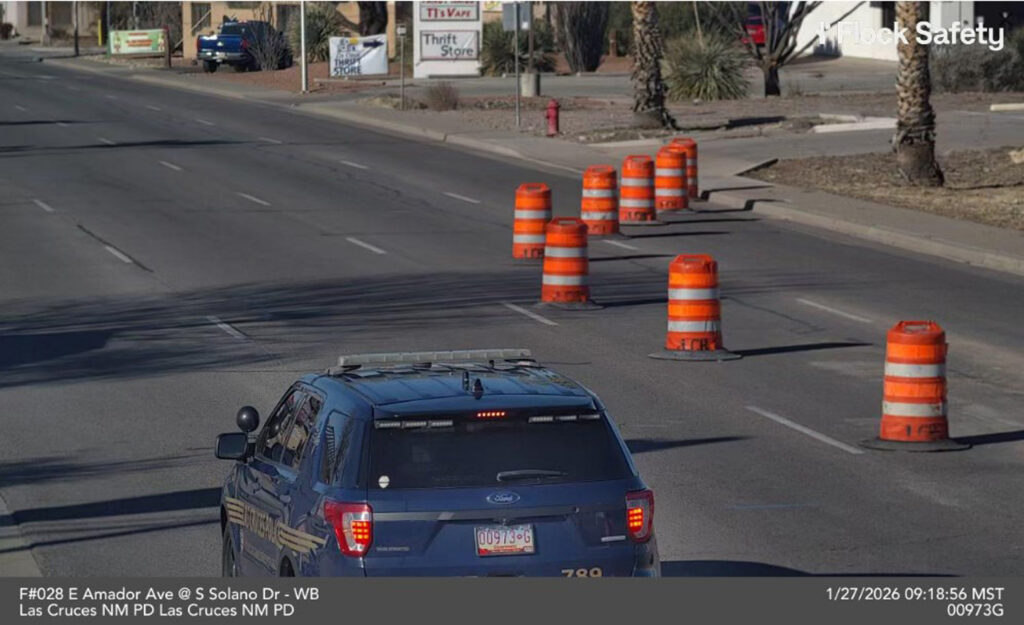

FULL ARTICLE: You’ll see cameras on your left and right as you’re driving past Pep Boys on Amador Avenue in Las Cruces.

The police cameras, which have solar panels mounted above them, are pointed west, the same direction traffic is heading. They’re not designed to photograph your face. They capture still images of the rear of your vehicle.

Such license plate readers, or LPRs, are becoming increasingly common across the nation. They’re owned by a private company, Flock Safety, and leased to police departments in many communities in New Mexico.

There are dozens around Las Cruces and Doña Ana County.

Chiefs from three area police agencies say LPRs are a critical tool. Las Cruces Police Chief Jeremy Story provided several examples of the cameras helping solve crimes.

In interviews, most Las Cruces city councilors acknowledged the role LPRs play in police work. Several also joined privacy advocates in expressing concern about abuse: Depending on guardrails implemented at the local level — or maybe even in spite of those protections, some fear — data the cameras capture could be used in ways that put residents at risk.

Through Flock, many local police agencies share data with federal agencies including Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Officials say that isn’t happening in Las Cruces. But in some communities, data from local police cameras that motorists pass on their way to work or their kids’ schools could be used to aid President Donald Trump’s mass deportation efforts.

ICE might also use such data to advance its growing surveillance of U.S. citizens who protest its actions or assist immigrants.

Many are also concerned about protecting women because of an instance of deputies in Texas searching Flock’s nationwide database as part of a 2025 investigation into a report of an illegal abortion.

Flock lets local agencies decide how to share their data and who gets access. The police chiefs I interviewed for this article said they don’t allow their agency’s data to be used for such purposes.

But there are provisions in contracts with the City of Las Cruces, Doña Ana County and New Mexico State University that let Flock share data, regardless of a local agency’s settings, in an emergency.

While Story recently added protections into LCPD policy, some are convinced that isn’t enough.

Two city councilors have scheduled a meeting with Flock to ask for additional protections in the city’s contract. A third plans to propose local regulations.

At the state level, pending legislation would place limits on the sharing of data collected by LPRs.

Even if the city or state enacts regulations, Councilor Michael Harris has suggested Las Cruces might want to store and manage its own data instead of paying Flock to do it.

“It is nice that we have policies that ‘prohibit’ information sharing, but it may be naive to expect that tech companies like Flock will respect them,” Harris told me. “The business model of surveillance capitalism is fundamentally opposed to community safety and privacy.”

Fighting crime

In Las Cruces, the LPRs are part of a $1.8 million investment in the city’s real-time crime center — a facility staffed by technicians who have access to cameras, drones and other data to assist police officers in the field.

The city has a contract with Flock for about $737,000 over five years as part of that effort. That money added to previous, smaller contracts for LPRs and expanded their numbers on city streets. The contract also includes installing video cameras in some city parks, integrating existing infrastructure like cameras on the outside of city and public school buildings, and software.

There were no LPRs watching over the parking lot at Young Park in Las Cruces during a shootout that left three teens dead in 2025. There are today.

Story says the real-time crime center is essential. He cited a situation in which a drone kept an eye on a prowler hiding in a shed in a backyard until officers arrived. He also spoke about a camera catching copper thieves in the act.

I experienced the technology’s capabilities last month. I called 911 after a man brandished what turned out to be a BB gun while teens were protesting federal immigration raids. The man fled in his vehicle, and the drone followed him until officers could catch up.

“These tools are for situations like this — to protect our citizens from being victimized and to help hold those who prey on people exercising their rights accountable,” Story said.

Outside the city limits, you’ll spot an LPR on the southeast corner of the parking lot at Aggie Memorial Stadium on the New Mexico State University campus. It’s one of seven placed at ingress and egress points.

NMSU interim Police Chief Justin Dunivan said the cameras have identified vehicles involved in burglaries and auto theft.

You’ll find cameras throughout Doña Ana County. There’s one near the onramp for the southbound lanes of Interstate 10 in Vado, next to a busy truck stop. Two watch over Lisa Drive in Chaparral, which is the primary east-west route through that growing community on our side of the state line just north of El Paso, Texas. There are LPRs pointing north and south on Highway 28 in San Miguel.

Sheriff Kim Stewart spoke glowingly about LPRs. She described one capturing a missing person’s vehicle heading to the Vado truck stop. That led investigators to ask for the truck stop’s security video, which revealed that someone else was driving.

Then the vehicle headed to El Paso, and a missing-person case became a multi-state homicide investigation that’s currently being prosecuted.

There are 45 LPRs in Las Cruces and another seven on the NMSU campus, according to Story and Dunivan. The sheriff’s department has 30 in unincorporated parts of the county, with more coming online soon, Stewart said. Public records indicate the county signed a contract for an additional 12 late last year.

Some corporations also lease equipment from Flock. LPRs watch over parking lots at Home Depot and Lowe’s Home Improvement in Las Cruces.

Flock says its cameras are in more than 6,000 communities in the United States. The website deflock.me has an open-source map of almost 72,000 Flock LPRs across the nation that’s considered generally accurate. It shows 55 in the Las Cruces area, and I verified many of them.

The map lists 332 in the greater Albuquerque area, stretching from Rio Rancho to Belen. It shows 37 around Alamogordo, 22 in Clovis, 16 around Hobbs, and 11 in Santa Fe. There are three dozen around Farmington, Bloomfield and Aztec.

The feds also contract with Flock. There are LPRs at all inland U.S. Border Patrol checkpoints in New Mexico. And there are two in front of the Border Patrol station on N.M. Highway 9 in Santa Teresa, not far from where Project Jupiter is being built.

Data protections

Data sharing with other departments is a “legitimate concern,” Story said. Flock offers strong privacy settings for agencies that want them, he asserted, and LCPD takes advantage of those options.

Flock lets agencies decide whether to share data with the federal government. LCPD only shares with local law enforcement agencies in New Mexico and El Paso and has “never shared with federal agencies,” Story said.

Agencies can disallow searches of their data related to immigration and reproductive care by their own officers and other agencies. LCPD disallows both types of searches.

LCPD opts to have data collected by LPRs stored for 30 days. That compares to the Albuquerque Police Department keeping data for a year, Story said.

To search LCPD’s data, an officer must have an account and log in. There’s a record of who is searching and what they’re looking for. LCPD audits searches.

Flock is also developing an artificial intelligence feature that, once implemented, will search for potential misuse of the system and flag it, Story said. Examples, he said, might be searches at “odd” times of the day or repeatedly at the same time each week.

“I think Flock is trying to respond to the public concern and pressure and build in systems that keep it secure,” Story said.

Stewart and Dunivan also expressed trust in the system. They said their departments don’t share with federal agencies.

“We’re focused on local crime and safeguarding our local community,” Dunivan said.

Eliminating loopholes

But abuse is possible. The American Civil Liberties Union of New Mexico points to a 2016 Associated Press investigation that found officers misusing “confidential law enforcement databases to get information on romantic partners, business associates, neighbors, journalists and others for reasons that have nothing to do with daily police work.”

Story acknowledged that police officers sometimes misuse systems. But he said the checks in Flock’s system are even more stringent than those in the National Crime Information Center, a database managed by the FBI of criminal histories, outstanding warrants, missing persons and other information.

“There’s the potential for abuse with any technology. Human beings can abuse things and do,” Story said. “…The guardrails are important.”

LCPD’s sharing with other agencies in New Mexico and El Paso may make sense from a law enforcement standpoint, but it raises another concern for the ACLU: Even though ICE can’t directly access LCPD’s data, agencies that do have access could share that data with ICE.

Las Cruces City Councilor Johana Bencomo helped spearhead an effort last year to strengthen the city’s protections for immigrants by updating the Welcoming City resolution. She joins Harris in doubting that the protections Flock offers are sufficient, “not because I don’t trust the chief and the safeguards in place locally, but because I don’t trust big tech and the current push from the federal government to turn over data and people.”

Councilor Cassie McClure said she and Harris will soon be meeting with Flock officials. She wants to discuss a provision in the city’s contract that allows Flock to use LCPD data for artificial intelligence training.

She’s also concerned about a provision that lets Flock share data, regardless of LCPD’s privacy settings, to “detect, prevent or otherwise address security, privacy, fraud or technical issues, or emergency situations.”

That catch-all provision is quite broad. McClure said she’ll be leaning on Harris’ technical expertise — he’s a computer programmer — in discussions with Flock.

Harris said he’s been voicing concerns since before he won a seat on the City Council last year.

“My priority is the safety, security and privacy of all Las Cruces residents,” Harris said. “We can find a balance of how much surveillance data to collect that fits the needs of our community.”

Flock’s contracts with NMSU and Doña Ana County include provisions like the city’s that let the company override agency preferences to share data with “law enforcement authorities, government officials, and/or third Parties” in certain situations, including a response to “an emergency situation.”

There’s been far less public scrutiny on the county’s contract with Flock than the city’s. The same is true of NMSU’s agreement. County Commission Chairman Manuel Sanchez said he needs to “get a little bit more educated on the agreement the county has with Flock.”

“But it’s a priority of mine to make sure that we are protecting the data that we have and that we are not going to be sharing that with ICE for immigration enforcement,” he said.

The ACLU notes that the Boston Police Department’s contract doesn’t let Flock override an agency’s privacy settings. The organization suggests local communities work to remove such provisions from their contracts.

“Every community in the nation that is home to Flock cameras should look at the user agreement between their police department (or other Flock customers) and the company,” the ACLU said in October.

Calls to cancel contract

McClure credited city residents with sparking the privacy conversation in Las Cruces. “Thanks to citizen engagement, step one has been to sit down with staff to see what guardrails are in place, and crucially, which are missing,” she said.

Three people asked councilors to end the city’s relationship with Flock at their Jan. 20 meeting.

“I urge the council to please delete this contract and remove the cameras from the Las Cruces community to keep our community safe,” Lucy Silva said.

“Many other cities have already stepped away,” said Jason Smith. “You have that option.”

More than a dozen communities in at least five states had suspended or paused their Flock contracts as of November, according to the news organization Politico.

“The problem is the federal government is going after a lot of people who aren’t doing anything wrong,” Politico quoted Marc McGovern, the vice mayor in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as saying after the city voted to pause its contract with Flock late last year.

McGovern said it wasn’t a problem to photograph his license plate because he’s a “56-year-old white guy.” But, he said, “They’re not coming after me.”

Flock installed additional cameras in Cambridge a month after the city paused the contract. The city called that a “material breach of our trust and the agreement” and canceled the contract, according to The Harvard Crimson.

Greater oversight

Las Cruces doesn’t appear to be headed toward shutting down its real-time crime center. Councilor Becky Corran cited two studies that demonstrate the benefits. “Chief Story has emphasized an evidence-based approach to policing, and the technologies within the RTCC are supported by evidence,” she said.

Bencomo is more skeptical. She asked hard questions before deciding to support the project, and she said she had “serious concerns about what expanded police surveillance technology would mean for our civil rights.”

Bencomo said was “shocked” to learn that LCPD wants another $3 million from the state to create a master plan for the real-time crime center and expand fiber-optic cable. She said other proven methods for improving public safety “don’t get funded to this level.”

But, Bencomo said, the existing investment and the political makeup of the council mean the real-time crime center is not “going away.”

However, some councilors are open to exploring a future without Flock. While McClure believes the real-time crime center is useful, she said, “if a system like Flock proves to be dangerous to residents, then it’s something that we might need to reexamine.”

Story is concerned that councilors might disallow the cameras. The city contracted for five years of service from Flock. That included federal funding secured by U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich to get the real-time crime center up and running.

Story believes LCPD has already shown the value of LPRs and the crime center, but he said he hopes to have the full five years to make the benefits clear.

Corran said the best path forward is “firewalling” the data the city collects by keeping it local to the extent possible, not storing it for too long, and training staff to understand data collection policies and procedures.

Storing and managing data locally, as Harris suggests, would be expensive, but there would be little concern about a corporation overriding city policy to give other law enforcement agencies access to its database.

“Collecting that kind of data is a big responsibility, which we need to acknowledge and own up to,” Harris said.

While McClure and Harris talk with Flock about the city’s contract, Bencomo said she will be developing “strong, model local legislation that protects our data from being sold to third parties or shared with federal agencies, enforces fiscal responsibility, and strengthens transparency through clear biannual reporting requirements.”

Meanwhile, Councilors Bill Mattiace and John Muñoz, the mayor pro tem, expressed confidence in the surveillance system, including the agreement with Flock. While acknowledging the need for strong oversight, Muñoz said the real-time crime center has already made a positive difference.

“These technologies help recover stolen vehicles, provide officers with faster investigative leads, and reduce the likelihood of escalated stops,” he said. “… Las Cruces can and should lead New Mexico in adopting technology and innovation that enhances both public and officer safety.”

Still, Muñoz is supportive of the conversation about privacy. “Human judgment, quality control and continuous improvement are essential to ensure these systems are used appropriately and responsibly,” he said.

State regulation

At the state level, Senate Majority Leader Peter Wirth is sponsoring legislation that would outlaw the use of LPRs for immigration enforcement, to pursue investigation or prosecution of activities that are legal in New Mexico like “protected health care activity,” or to “identify or impose civil or criminal liability” on someone for exercising their constitutional rights.

Senate Bill 40 would require agencies to report quarterly about requests for information collected by their LPRs from out-of-state parties.

Those who intentionally violate the act could face fines of $10,000 or actual damages, whichever is greater.

Wirth, a Democrat from Santa Fe, said there is “great value” in LPRs, “but it is imperative that we have the guardrails in place to ensure that the data being collected isn’t being used or sold in ways that conflict with the values or laws of New Mexico.”

He said the legislation is “just the beginning of an ongoing effort to mitigate the kinds of unintended consequences that these tools might have.”

Two Senate committees have advanced the legislation, the last on a unanimous, bipartisan vote. SB40 awaits a vote by the full Senate. It would also have to make its way through the House before the current legislative session ends at noon on Feb. 19.

Story said he’s talked with the ACLU and Flock’s lobbyist about SB40. With a few changes, he said, the legislation “could be a good thing that might ease some of the concerns.”

The chief said he’s similarly open to the City Council enacting an ordinance that mandates privacy protections like those he’s already implemented.

‘New Mexico has a problem with crime’

Story ultimately believes Flock has financial incentives to honor its agreements and isn’t as concerned about privacy as some others interviewed for this article. He urged policymakers to keep focus on the reason police are using LPRs.

“New Mexico has a problem with crime,” he said. “I think everyone has to acknowledge that.”

The chief pointed out that some city parks, like Sam Graft Park on the city’s east side, are safer than others, like Young and Apodaca parks in the center of the city.

“I don’t think it is OK to be inequitable in that way,” Story said.

Young and Apodaca will both soon have live video cameras that technicians in the real-time crime center can utilize. That will help increase access to safe parks for nearby neighborhoods, the chief said.

The 45 LPRs spread out across the city’s 77 square miles capture only moments in time, Story said. It’s not possible to use them to reconstruct people’s movements, he asserted, and he’s not pushing to add more LPRs.

He remains insistent that the benefits far outweigh the costs.

“I think most people are going to feel safer having them, not less safe,” he said.

Did you learn something from this article? In-depth reports like this take a lot of time and hard work, and I need your help to keep doing them. If you’re able, make a donation by clicking here. Even a few bucks makes a difference! Thank you!

The documents

Here are the government documents used as sources for this article:

Las Cruces Police Department

• Newest service agreement with Flock Safety (includes purchase agreement for equipment added during creation of real-time crime center in September 2024)

• December 2021 purchase order for additional 12 LPRs

• January 2021 service agreement and purchase order for initial 10 LPRs

• License plate reader policy (as of Sept. 11, 2025)

• Recent updates to LPR policy

• Presentation on LPRs

• LCPD Bridging the Badge episode on real-time crime center

Doña Ana County Sheriff’s Department

• Service agreement with Flock Safety

• 2023 purchase order for 30 LPRs and four mobile LPRs

• 2025 purchase order for additional 12 LPRs

New Mexico State University Police Department

Thank you.

For the reporting? You’re welcome if that’s what you mean!

After just watching the U.S. Attorney General trash any positive view I might have had to trust Federal law enforcement agencys, I’ve become less trusting of anything I’m told or promised by most officials. LPRs are helpful to catch criminals but restrictions on who gets, and what they do with the data are essential. And will lawful restrictions be followed?

Good question! Thanks Fred.

Articles like this are why I donate to Heath Haussamen. Thank you for doing the investigation and for providing links to the source documents.

You’re welcome! Thanks for your support and your kind words!

Depth of reporting. That’s what we need and it is what you do. Excellent read.

Thank you, Del!

For the record: I contacted Councilor McClure on September 10, 2025 asking her if we could organize a community meeting regarding Flock. That was almost 6 months ago now and she has since stopped answering my messages and questions entirely. She went as far as to tell me that councilors can’t bring forth resolutions for consideration and refused to discuss my draft. I wrote and submitted a Flock contract cancelation resolution that Cassie flat out ignored. To hear that she’s taking interest now is disingenuous; she cares more about not rocking the political boat instead of actually representing constituents.

For the record: Bill Mattiace lied to me when he pledged to call a list of cities I listed during public comment on January 5th, 2026. Councilor Mattiace sent me an email on 1/6 stating: “let me contact city administrators form your cities cited as well as the cities that have continued using the security system especially border cities”. Instead, during a phone call on 2/6/26, he turned on his used car salesman scheme. He started off by telling me he doesn’t get paid enough for his work on the bench. He told me a long winded story about calling his cousin who is a police officer in New Jersey. Odd thing is, even the cop cousin told Bill that he has problems with flock – yes, his own family agrees they are bad!! Mattiace never did what he said he would do, never answered ANY questions on my multiple emails to him and council, and then last night sent me a rude email declining to answer the very questions HE pledged to investigate and instead telling me that “he’s done”.

Contact me for the phone conversation and emails if you’d like to see for yourself.

Councilor Mattiace is a lying, scummy used car salesman protecting his self interests and nothing more.

Flock taps into school cameras: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/feb/10/ice-school-cameras-police-license-plates