THE DOCUMENTS: Find links to the final agreements between Doña Ana County and Project Jupiter’s developers at the end of this article.

Documents that authorize tax breaks for the developers of Project Jupiter totaled 359 pages on Sept. 19, the day Doña Ana County commissioners voted publicly to approve them.

When Commission Chairman Christopher Schaljo-Hernandez signed the final legal agreements on Oct. 30, those documents had grown to 1,583 pages, by my count.

The increase in pages as negotiators worked in private illustrates the N.M. Foundation for Open Government’s assertion that the process of approving the incentives to entice construction of the massive campus of data centers in Santa Teresa violated the state’s Open Meetings Act, and is thus invalid.

That’s because the pair of 4-1 votes on Sept. 19 to approve the agreements was the last time four of five commissioners and the public had any say in them. Commissioners voted that day to let Schaljo-Hernandez negotiate and execute final changes in secret, even though the state law requires that policy be finalized in public so you can watch.

It wasn’t until late last week — nearly six weeks after Schaljo-Hernandez signed the documents and more than 11 weeks after commissioners voted — that the county released final agreements to the public and we got to see the extent of the changes.

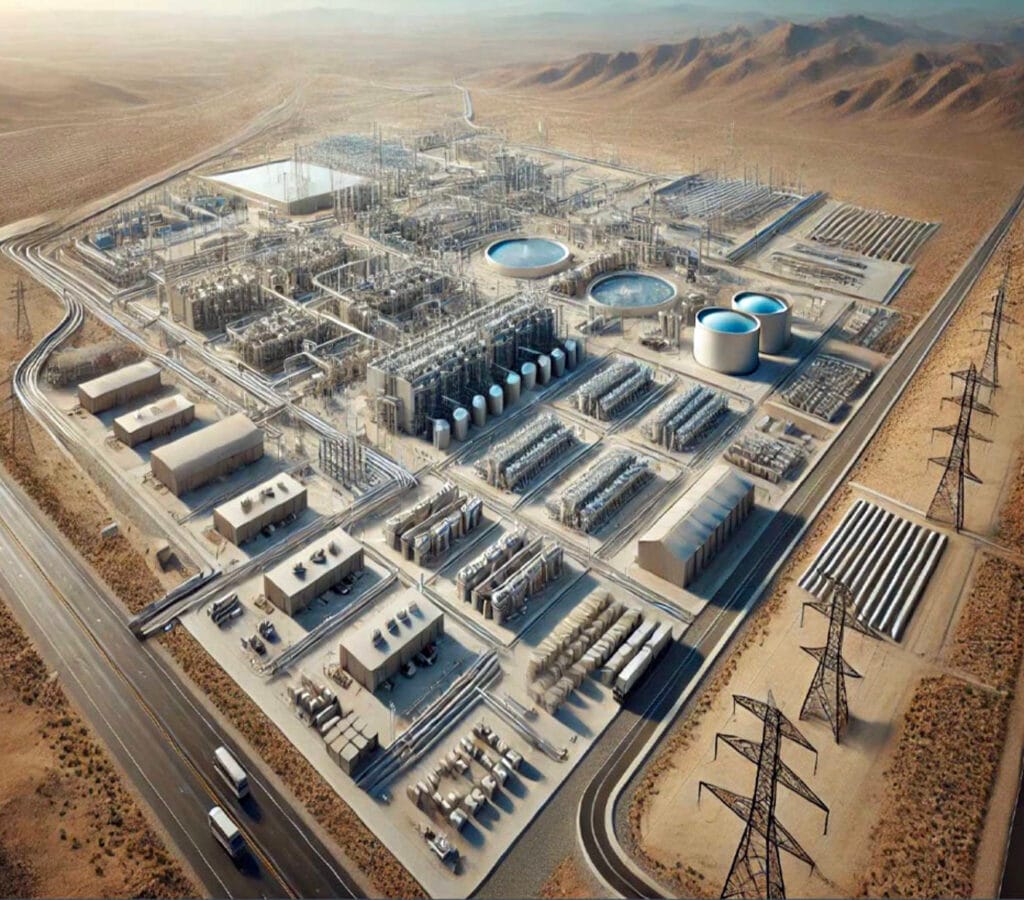

In the months since commissioners voted, the number of pages in the agreements grew exponentially. There’s new language in many sections of the documents, which authorize a 30-year exemption from paying property taxes through a complex, $165 billion industrial revenue bond agreement, and a partial exemption from paying gross receipts tax.

Also included are entirely new documents. Those include letters from attorneys defending the county’s process as it battles two lawsuits that seek to undo the property tax exemption. And they include a “community benefits agreement” that immortalizes the developer’s promises on water use and donations for local needs, among other things.

The letters and community benefits agreement are each included three times in the final documents, so redundancy is responsible for some of the increase in the number of pages, but not all. Regardless, they’re still pages folks have to sort through to gain a full understanding of the agreement.

Christine Barber, FOG’s executive director, said this is not how a representative democracy works.

“This is a government that the people are no longer a part of,” Barber said of Doña Ana County. “… The people have a right to have been a part of this, and they weren’t. They were denied that right.”

Language changed

Schaljo-Hernandez promised that he would honor the intent of what commissioners approved on Sept. 19 as he finalized the agreements. To the extent that commissioners understood what they were approving when they voted on documents that were labeled as drafts and were missing pages, that seems true. The developers’ biggest public promises are in the community benefits agreement.

But there were some dramatic changes in the structure of the documents. For example, on the day of the 4-1 votes, many of those promises were included in a memorandum of understanding that stated it was not legally binding. Now language in the community benefits agreement ties those promises to leases for the data centers and appears to make them legally binding.

While the end result may be positive, Schaljo-Hernandez has executed an entire legal agreement the public has never seen and commissioners never discussed or voted on publicly.

The changes from the versions of documents the public and other commissioners saw are not insignificant.

For example, when commissioners voted on Sept. 19, they approved language that promised a limit on Project Jupiter’s water use. “The daily operational water use for the full data center campus buildout will be an average of 20,000 gallons per day with a maximum peak use capped at 60,000 gallons per day,” the MOU stated.

The executed community benefits agreement adds the word “potable” to the language, limiting the “daily operational potable water use” to those numbers.

Commissioners have had no public discussion about the addition of that word and why it was necessary.

Water use still in question

In the rush to approve the agreements in September, county officials have also failed to gain a shared understanding of the legal promise on water use.

I asked Stephen Lopez, the assistant county manager who’s been heavily involved in negotiations, if the pledge to use no more than 20,000 daily gallons on average, with a peak of 60,000 per day, includes water needed to operate two microgrids that will power the data centers.

It does not, he said. Project Jupiter will use water beyond those numbers for power generation.

“My expectation is that the limits in the section you quote relate just to the data center buildings, and not the power generation facility,” Lopez said. He added that Project Jupiter will be bound by a similar limit — an average of 20,000 gallons per day — for the microgrids, bringing its total average daily water use to 40,000 gallons.

That’s not how Schaljo-Hernandez and another commissioner who voted to approve the agreements, Manuel Sanchez, see things. Both told me this week that the agreements limit total water use, including for power generation, to an average of 20,000 gallons per day and a maximum peak use of 60,000 gallons per day.

Both held firm even when I shared Lopez’s comments. They asserted that the industrial revenue bonds include construction of the microgrids, so the microgrid water use is bound by that agreed-upon limit.

“That is what this Commission will be holding them to,” Schaljo-Hernandez said. “…That is what I will be holding them to.”

With the county in the process of taking over the region’s water utility, Sanchez said, “if there’s going to be any deviation from that… we have the ability not just to shut off the water, but if they were to grossly use water way past the limits, we have the ability to hold them in breach of contract per the IRB documents.”

Confusion illustrates the point

I’ve been trying for days to reach officials at the Camino Real Regional Utility Authority, which is responsible for permitting water use until the county takes over operations, to learn how much water use they’ve approved. My calls and emails have gone unanswered.

And officials with BorderPlex Digital Assets, one of the companies behind Project Jupiter, have not responded to two emails seeking comment on this and other issues.

On Sept. 19, the chairman of BorderPlex Digital publicly threatened to take Project Jupiter elsewhere if commissioners didn’t approve the tax incentives that day. That sparked the county’s rushed process. Now that company officials have their tax breaks, it’s become difficult to get information from them.

Whether we’re talking about 20,000 gallons per day or twice that, Project Jupiter’s water use stands in stark contrast to the allowable water use the City of El Paso recently granted Meta for a nearby data center being built in Texas just across the state line from the large, unincorporated community of Chaparral in New Mexico.

Meta can use up to 1.5 million gallons of water per day for that facility, and El Paso estimates it will use an average of 400,000 gallons per day, according to the news organization El Paso Matters.

Regardless, I’d like to think a public discussion between commissioners and the developers about the full documents on Sept. 19 — after the public had a chance to read them, ask questions and provide input — would have clarified the meaning of the language on water use.

Instead, nearly three months after its formal votes to approve drafts, our county government still doesn’t have a uniform understanding of its own agreements.

Calls for a new, public vote

Asked about the confusion over water use, Commissioner Susana Chaparro, who cast the only vote against the agreements on Sept. 19 because she was unwilling to approve drafts, called for a new vote.

“We’re still, even at this point, lacking concrete information, and this document is ever-changing,” she said. “I’d like to be able to take a public vote on the changes and the issues that are coming up so that the public can be informed, and so they have a voice.”

FOG says a new vote is necessary to correct Open Meetings Act violations and legalize the documents.

In the meantime, Barber said county residents are fortunate the disagreement is over 20,000 gallons of water per day when it could have been 500,000.

“I just feel so bad for the people of Doña Ana County. They haven’t had a voice in this,” Barber said. “…I don’t know how the people of Doña Ana County are ever going to forgive their county commissioners. I don’t know that they should.”

Read the final agreements

At any rate, here are the final documents:

• Industrial Revenue Bond Series A (includes community benefits agreement at the end)

• Industrial Revenue Bond Series B (includes community benefits agreement at the end)

• Industrial Revenue Bond Series C (includes community benefits agreement at the end)

• Local Economic Development Act agreement

• Memorandum of Understanding

• Resolution 2025-96

• Resolution 2025-99

• Ordinance 367-2025

• Ordinance 368-2025

• Ordinance 369-2025

Disclosure: My spouse, state Rep. Sarah Silva, is a supporter of Project Jupiter.

When this was coming up for a vote, I asked three different AIs how much pollution the nearly gigawatt natural gas grid would produce if they used the most efficient new natural gas generators. They all agreed that it would equal about 500,000 cars.

There was a flaw in my prompt though. When they construct these “microgrids” as they have in Texas, they don’t use the latest, cleanest generators, because there is a seven year backlog to get those! They buy what’s available, and that’s quite dirty natural gas generators.

Good thing we have their actual numbers now: https://sourcenm.com/2025/12/05/data-center-project-jupiters-greenhouse-gas-emissions-could-rival-nms-largest-cities/

I would like to see Tessa Abeyta go on record as a new rep for BorderPlex. Project Jupiter has tapped Tessa for her political rolodex and I’m sure Shannon Reynolds is next. It is concerning that Abeyta came directly from Senator Heinrich’s office. Also concerning that she led the NM Public Health Association as Executive Director before all of this – an org that supposedly defends against environmental and transparency failures such as the one she is now a part of. Let’s grill these folks so that their golden parachutes don’t look so sexy after all.