LEARN MORE: Catch up on my previous coverage of Project Jupiter:

Developer must guarantee Project Jupiter’s rosy promises (Sept. 3)

Project Jupiter agreements must protect water, residents (Sept. 8)

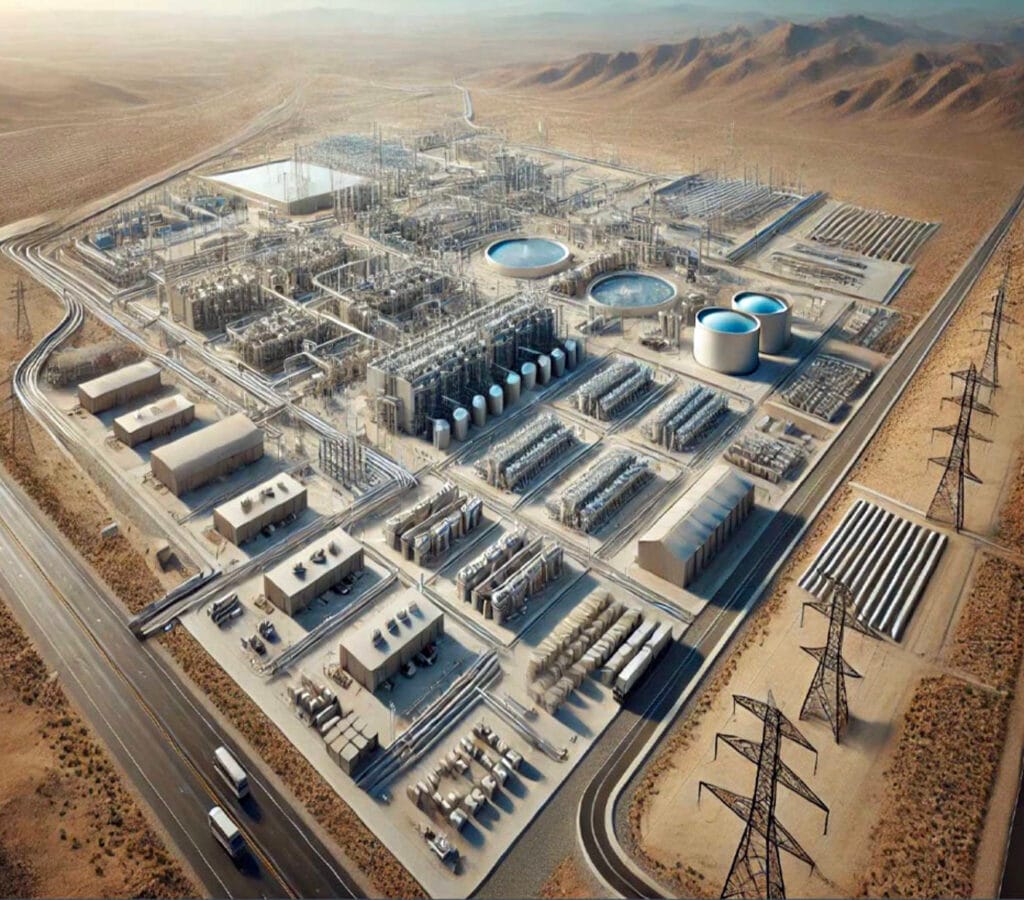

At least two local government agencies have signed non-disclosure agreements with the developers of Project Jupiter, the massive and rapidly advancing proposal to build a campus of data centers in Santa Teresa.

I don’t yet have copies of the NDAs that Doña Ana County and the Camino Real Regional Utility Authority entered into with the developers, but I have verified that both exist. What those agreements require from government officials isn’t yet clear to me.

I’m also trying to learn whether any other government agencies have signed such agreements. I have submitted requests under the state’s Inspection of Public Records Act (IPRA) to several agencies and am awaiting responses.

Staff at the utility, which is commonly called CRRUA, disclosed the existence of their NDA to their governing board and the public at a meeting on Monday and answered questions about it.

Doña Ana County, on the other hand, hasn’t yet decided whether it will release its NDA to the public — and until it does decide, staff won’t discuss it.

“One of the questions we are in the process of determining is whether the NDA itself is protected under the IPRA exceptions, so we will not be able to provide it or specific information concerning the NDA at this time,” County Attorney Cari Neill told me.

The revelation that public agencies have agreed to such secrecy is concerning, said Christine Barber, the executive director of the N.M. Foundation for Open Government (FOG). She questioned the reason for the NDAs given that state law already dictates what’s public information and what government agencies can keep secret.

To add to the concerns, a Doña Ana County commissioner’s statement raises questions about who authorized the public agency to enter into a confidentiality agreement.

“I was not aware of an NDA until I inquired about it,” Commissioner Susana Chaparro told me Wednesday. She said her inquiry came shortly before the Commission’s Aug. 26 meeting, which was the first time commissioners publicly discussed Project Jupiter. County staff had already been negotiating with the developers for weeks before that.

“It is my belief that the commissioners should have been alerted before the NDA was signed,” Chaparro said.

She said she can’t answer additional questions at this point. But it’s noteworthy that at the Aug. 26 meeting — when Chaparro cast the lone vote against advancing proposed tax incentives for Project Jupiter — she hinted that she hadn’t been fully included in the process.

At that meeting, Chaparro said she had met twice with the developers, for a total of two hours. While staff told her that was more time than any other commissioner had spent with them, Chaparro said she did not believe that and still did not have all her questions about the project answered.

I can’t tell you who signed the county’s NDA. That is among the reasons the county should release the document, Barber said.

“The public needs to know it exists,” Barber said. “They need to be able to see a copy of it so that we can see what it says. … Everyone should have questions about this.”

Fueling public skepticism

County commissioners and the developers of Project Jupiter are already facing intense scrutiny and backlash from some in the community. The NDAs raise questions about compliance with the state’s transparency laws, which could increase criticism.

Much of the skepticism about Project Jupiter comes because of the history of development projects in the area that includes Santa Teresa and the nearby City of Sunland Park. Folks there have dealt with environmental pollution caused by the now-demolished ASARCO plant across the state line in Texas, in addition to a landfill and, most recently, a long-standing problem with unsafe levels of arsenic in their water.

Now those same people are being asked to trust government to negotiate a deal with out-of-state corporations that plan to use natural gas as a power source and consume some of the region’s precious groundwater.

Several people who live in Sunland Park and Santa Teresa traveled to Las Cruces on Tuesday to speak against the project at a county commission meeting. They included Jose Saldaña of Sunland Park, who said when he was younger he had lead in his lungs.

Calling himself “a survivor of ASARCO,” Saldaña said he worries Project Jupiter will leave the region in ruins.

“We’ll be in the worst drought. We’re gonna have to leave, and they make their money and they’re gone,” Saldaña told commissioners. “…It’s ridiculous what you guys are doing to us.”

I’ve already written that I am inclined to support Project Jupiter as long as legal agreements guarantee low water use and commit the developers to pitching in tens of millions of dollars to improve the water and wastewater system in the area. We haven’t yet seen documents that would commit developers to those things in writing.

I obviously haven’t been affected by government’s history of failing people in the region like Saldaña has. Government agencies that sign NDAs with corporations are already asking a lot by expecting folks to trust them in spite of the fact that they’re agreeing to keep information from them.

And if Doña Ana County decides to take the secrecy even further by refusing to show the public its NDA? To keep secret a document that details which information the county has promised to keep secret?

That will be difficult for many people to swallow.

CRRUA’s disclosure

When CRRUA staff disclosed their NDA on Monday, they made clear they intend to comply with state transparency laws.

CRRUA Attorney Adán Trujillo told board members that staff had signed the NDA with Stack Infrastructure, one of the developers of Project Jupiter, only after making amendments to the agreement that were “received and acknowledged” by Stack.

Those changes stipulate that CRRUA is legally required to comply with IPRA. Stack understands that if CRRUA receives a records request for documents it’s legally required to release, it will release them, Trujillo said.

Because of that, Trujillo said the agreement is mostly symbolic.

“I think the burden is more on the company to not disclose things to CRRUA that they don’t want the general public to see,” he said.

Why did Stack want an NDA? Stack would be the builder of the data centers. But the yet-to-be-named end user is likely a massive corporation like Microsoft, Meta or Oracle. Trujillo told board members that Stack may want to keep information relating “to the potential tenants or sub-users of the proposed development” secret “to the extent possible.”

Sunland Park Mayor Javier Perea, who chairs the CRRUA board, told me on Wednesday that the utility was determined “to make sure that we followed the law.” In an interview, he said CRRUA Executive Director Juan Carlos Crosby signed the NDA, which Perea confirmed he has seen.

I asked if he could expedite my request for a copy of the NDA, given the county’s rapidly approaching votes on tax breaks for Project Jupiter on Sept. 19. Perea said he is currently in Mexico and would get back to me.

CRRUA isn’t involved in approval of the data center campus. Its only role would be providing water and wastewater services. The county, by contrast, has final say in approval and has been in negotiations with the developers since before Stack revealed itself publicly to be one of them.

NDAs are a growing trend

Confidentiality agreements are a growing trend in public/private partnerships, particularly in the data center industry. Earlier this year, a professor and a student at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia, teamed up to file records requests in dozens of Virginia communities that had existing, approved, or proposed data centers. They found that 25 of 31 government agencies had NDAs.

“We think that this could be an underestimate because some local governments may use definitions or maneuvers to avoid disclosing this information,” sociology professor Eric Bonds and undergrad Viktor Newby wrote in a column for the Virginia Mercury published in April.

“For instance, one county reported that officials signed an NDA with a major tech firm, but they did not retain a copy for public record,” they wrote.

The authors said they had “naively assumed that NDAs were narrowly drawn guarantees that local governments would not share a company’s proprietary technology or cutting-edge trade secrets.” Instead, they discovered broad agreements that prohibited sharing business plans and “non-public information” — categories that could include “almost anything, including information that relates directly to community impacts.”

The agreements acknowledged that government might be required to disclose information in response to public records requests, they wrote. But those agreements also often “call on officials to share as little as legally possible, while giving the data center company advanced notice to intervene with its legal team if it so wishes before any information is shared.”

“In this way, NDAs are written to privilege secrecy over transparency in data center development,” the authors wrote.

Who are officials representing?

That had me thinking about a choice Doña Ana County made before its Aug. 26 meeting to exclude the developers’ application for bond financing from the documents it shared with the public — even though the county normally releases documents related to items on meeting agendas before the meetings.

This time, the county instead included a sheet of paper stating the application “has been withheld” to protect the developers’ trade secrets. It said the application would be released with redactions “upon request.”

While I later requested and received a redacted copy, the extra step was unusual, and arguably in conflict with the spirit of state law. IPRA makes it the official policy of government to err in the other direction: “…all persons are entitled to the greatest possible information regarding the affairs of government and the official acts of public officers and employees.”

Did the county make it more difficult to obtain the application because of the NDA?

It’s a fair question. Michael LaFaive, senior director of the Morey Fiscal Policy Initiative at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, wrote recently that such NDAs create a trust problem.

“Do elected officials represent taxpayers or corporations? This question shouldn’t have to be asked, but the rise of nondisclosure agreements in negotiations over tax incentives and subsidies makes it necessary,” LaFaive wrote in a 2022 column in the Washington Post.

The counterargument

Of course, there is a competing interest. I dug into why companies seek such secrecy in 2017 when I was investigating agreements between Spaceport America and Virgin Galactic. As I wrote then, the commercial space industry is hypercompetitive. Officials argued that publicly releasing information like rent payments and lease agreements could harm the spaceport’s efforts to recruit companies.

The data center industry similarly involves massive companies that are in fierce competition with each other for business and working to develop technologies to improve speed and capacity while also reducing water use and carbon emissions.

Doña Ana County Commissioner Manuel Sanchez was the first to confirm for me that the county had signed an NDA with the developers. His elected position means he has also served on the boards of the N.M. Spaceport Authority, which oversees Spaceport America, and the Mesilla Valley Economic Development Alliance (MVEDA).

Sanchez understands the reasons for confidentiality agreements. He said many companies in negotiations with MVEDA want anonymity. To be included in and proactive during MVEDA negotiations, Sanchez said he has agreed to NDAs in the past. He would like to see the same thing happen with the spaceport so he can participate in those negotiations.

Sanchez said he didn’t know many details about the county’s NDA with the developers of Project Jupiter, including who signed it or what it protected.

He answered all of my questions about the data center proposal and didn’t appear to be constrained by the NDA. When I pointed that out, he said he wanted to be transparent with the public.

CRRUA’s disclosure is ‘a good idea’

Similarly, Doña Ana County Commissioner Gloria Gameros answered all of my questions about the NDA and Project Jupiter, even though she says she was told by county staff that the NDA bound everyone at the county, including commissioners, to some level of secrecy.

Gameros said she hasn’t seen the NDA and doesn’t know who signed it or exactly what it requires. She said she doesn’t know which company is the end-user of the proposed data center project.

When I asked if she felt limited in what she could share with me or the public about Project Jupiter, Gameros said, “No, and the reason for that is I think the company is starting to loosen up.”

Stack and BorderPlex Digital have been holding community meetings in recent days and releasing more information about their plans related to power and water use, among other things.

Gameros is a supporter of Project Jupiter. The county is only collecting $17 per year in property taxes for the land where it would be built, she said — so the $300 million the developers propose giving the county over 30 years is exponentially better.

I shared FOG’s concerns about the confidentiality agreement with Gameros. She is the only county commissioner on the CRRUA board, so I also asked her about the different ways the two governments are handling the NDAs.

She said CRRUA disclosing its confidentiality agreement is “a good idea,” especially because the utility “has not had a good track record of being transparent or sharing information.”

And the county? Gameros said she’s trying to focus on access to health care, and her south-county commission district has been the focal point of some consuming issues lately, including Project Jupiter and the recent flooding in Vado.

In other words, she’s been really busy. Commissioners work part-time, and Gameros said she has to lean on county staff often.

“I trust in our legal to point us the right way,” Gameros said. “Not knowing the legal aspect of this… I can’t really say whether they did it right or not.”

Gameros said she doesn’t know whether the county should release its NDA.

What state law requires

Amanda Lavin, FOG’s legal director, said state law does not prohibit government agencies from signing confidentiality agreements. But those agreements can’t require anything that conflicts with IPRA. She called that “a fairly straightforward issue.”

“You can’t negotiate away the status of IPRA,” Lavin said.

The county’s situation also raises questions about compliance with the N.M. Open Meetings Act. If county commissioners agreed to enter into an NDA, state law would require they do it in a public meeting with a quorum of at least three of five members present, she said.

That didn’t happen.

But Sanchez and Gameros said they didn’t participate in negotiating or enacting the agreement — even though Gameros said staff told her it applied to her.

Does that mean staff negotiated and agreed to the NDA without commission knowledge or approval? That might match with what Chaparro said as well.

It’s not clear that County Manager Scott Andrews, who reports to county commissioners, or any other county staffer has the authority to negotiate an agreement that binds commissioners, Lavin said. But without seeing the NDA, she said it’s difficult to determine if anything was done improperly.

Which brings us back to the NDA itself. Lavin agreed with Barber that the county needs to release it. “There’s no exemption in IPRA for non-disclosure agreements or confidentiality agreements,” she said.

The stakes are high

Clearly, the use of public/private NDAs, while the number is unknown, is “widespread,” LaFaive wrote three years ago. It’s important we know what the NDA requires from Doña Ana County because of what’s at stake.

Officials are considering exempting Project Jupiter from paying property taxes for 30 years and giving it other tax breaks to convince the developers to locate a campus of data centers in Santa Teresa that promises jobs. In exchange, Doña Ana County is set to receive the $300 million payout.

Other terms are being negotiated. We don’t yet know them all. And we don’t have written commitments, at least publicly, from the developers on water use or their public pledge to help improve drinking water in the Sunland Park/Santa Teresa area.

The county is set to release proposed agreements with the developers in the coming days. Assuming the county complies with IPRA, we should have access to all information in the proposed agreements at that point.

Commissioners and the public should have time to review the agreements before the Commission’s scheduled votes on Sept. 19.

In some states, the public hasn’t learned about the terms of such agreements until after they’re approved. Again, assuming the county complies with IPRA, that won’t happen here because New Mexico has strong transparency laws.

Still, LaFaive’s bottom line is worth noting, given the yet-to-be answered questions about the county’s NDA:

“While companies and politicians say that NDAs protect sensitive negotiations, the NDAs help ensure that companies’ potential big paydays aren’t sunk by unwanted publicity,” LaFaive wrote.

I will keep you updated on my efforts to obtain and learn more about these confidentiality agreements.

DISCLOSURE: My spouse, state Rep. Sarah Silva, participated in negotiations related to Project Jupiter. To preserve my ability to report on Project Jupiter and my spouse’s ability to do her job, I will not use anonymous sources in my articles about this topic. I will continue to report using documents and named sources only.

Engaging the public is key to developing support for big projects with multiple stakeholders. When different groups with varied interests and concerns have a voice in important decisions they more likely to bring support to these kinds of public-private partnerships. Glad you’re healthy again and committed to watch dogging the Jupiter Project. Keeping the process open to public scrutiny should be a win-win and a benefit to the local economy for 30 years and beyond if everything is righteous and above board.

Thanks!

Mr. Haussamen, Great work covering this very important issue. I think my opinion aligns with yours regarding potential benefit to the community – and it’s not like AI will diminish until it wipes out humanity by lethal force anyway. I DO NOT LIKE the NDA/hide-from-the-public shenanigans baked into this land use application process. Will every future applicant pull the same stunt or is this practice reserved only for $165 Billion projects?

What this will mean for future applicants is a great question!

Speaking as a citizen, who happens to be an attorney, I find the idea of an employee having the right to sign a non-disclosure agreement and keep secrets from the employer legally absurd in the context of private employment. I haven’t pulled case law (yet), but as to a public employee it seems so outrageous it verges on traitorous. We don’t use “master servant” language in employment law now, but the hierarchy hasn’t changed. While I have not come to a conclusion on the Jupiter Project, I find it easy to conclude that if this level of secrecy is required before approval, it’s dangerous for local democracy.

I hear you, and I appreciate you weighing in. Thank you.