There’s a wild place not far from Spaceport America where oryx eat the young, green stalks growing out of yuccas in the spring.

The imported African animals hide among the sand dunes, graze around low-lying areas where rainwater collects, and escape through wide arroyos when humans get close.

While hunting oryx there in 2024, my dad and I discovered the greatest concentration of pottery and other signs of the ancestors I’ve encountered.

Potsherds were scattered across dozens of square miles of dunes and arroyos. On several high points I spotted pieces of chipped rock left behind when someone made arrowheads.

On the edge of an arroyo we found a circle of compacted earth covered in potsherds — clearly a place where people gathered, and maybe even camped, long ago. The circle of trampled ground remains visible even though rain has fallen on it and water has flowed past it for hundreds of years or more.

Why did humans frequent a place that’s so dry? As we tracked oryx I pondered this question, and I began to see the land differently. Before cattle grazing, this was likely grassland. Water flowing off the San Andres Mountains likely slowed through this area, creating ponds and depositing sand that would become today’s dunes.

Spending time in this place gave me a glimpse of life before we destroyed so many ecosystems across the West. It instilled in me hope for what’s possible.

U.S. Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, wants to put a “for sale” sign on this place, and so many others like it.

A giveaway for the wealthy

Lee, who chairs the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, inserted into President Donald Trump’s gigantic welfare-for-oligarchs bill a requirement that the federal government sell approximately 2-3 million acres of land managed by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management.

Land would be selected from among more than 250 million acres in 11 states including New Mexico. The Wilderness Society has created a useful map that shows what areas would be up for grabs if the proposal is enacted.

Lee says the land selloff would address the nation’s housing crisis by freeing up land for construction. If it’s housing most of us can afford that Lee is talking about, this is a bald-faced lie. The cost of getting infrastructure like roads, electricity and sewer lines to many of these areas is prohibitive. Infill development in existing cities is much cheaper and more practical.

And in places where public land borders cities, like Las Cruces, federal agencies already have the authority to trade and sometimes even sell land to encourage development.

What Lee actually intends is an end run around existing requirements for public notification and input before giving billionaires a chance to own some of the most majestic land in the United States.

Land like the mesas above Jemez Springs that are currently part of the Santa Fe National Forest. I spent time there earlier this month and stared up at Mesa De Guadalupe, Mesa Garcia and Guadalupita Mesa, which are also on the Wilderness Society’s map of lands on Lee’s list. While I was fly fishing, I looked up at the mesas and thought about Lee’s buddies who might like to own multimillion dollar homes on the edge of those high cliffs.

As the oligarchs’ California homes fall into the ocean and their Florida homes are washed off beaches because of rising ocean levels and more severe storms driven by climate change, they’ll be looking to rebuild in places with majestic views and greater stability. Why not above Jemez Springs, with its grand views of red and cream cliffs and the river far below?

Special places and memories

We cannot let this happen. Selling off Forest Service and BLM land to the highest bidder would do more than take those lands out of the public domain. It would cut off access to wilderness areas and other places with greater protection, which usually can only be accessed through BLM or Forest Service land.

In New Mexico, we’ve made great strides in recent years with our outdoor equity fund and other state efforts to increase access to and appreciation for public lands. Lee’s proposal would do the opposite — locking our land up behind homes built by and for the wealthy.

Also on the list of land that could be sold in the Jemez Springs area is the Seven Springs Picnic Site and much of the land around it. The tiny Rio Cebolla flows gently through a meadow east of the picnic area.

I fished this river with my dad when I was young. He and my grandfather fished it before that. I returned there with my fly fishing rod last week and caught my first trout in years.

I have so many other stories about places and memories Lee’s proposal threatens.

Town Mountain in Sierra County, where I harvested my first deer.

The Tortugas Arroyo system east of Las Cruces, where I learned to hunt quail.

Tonuco Mountain north of Las Cruces, where my spouse Sarah and I found petroglyphs in a canyon and I photographed yellow cactus flowers in an arroyo.

Pine Flat Mountain in the Gila National Forest, where I took Sarah on her first backpacking trip.

These places are all on Lee’s list.

‘God isn’t making any more land’

So many folks have stories like mine about public lands that Lee proposes putting up for sale. Many people are rising up to oppose this theft.

On social media I’ve seen hunters criticize Republicans who support Lee’s efforts. I’ve seen conservatives express concern that the newest version of Lee’s proposal does not exempt lands with grazing leases from being considered for sale.

Idaho’s two U.S. senators, both Republicans, are among those who oppose Lee’s proposal. Lee excluded land in Montana from the selloff after consulting with that state’s two U.S. senators, also Republicans, who expressed opposition.

And a less expansive provision to sell thousands of acres public land in Utah and Nevada has already been stripped from the House version of Trump’s thieving bill thanks to bipartisan opposition from a coalition led by U.S. Rep. Gabe Vasquez, D-N.M., and U.S. Rep. Ryan Zinke, R-Mont.

As Zinke said on social media a few days ago, “God isn’t making any more land. Once it’s sold, we’ll never get it back.”

Drawing a line in the sand

Lee’s proposal is in limbo at the moment. The Senate parliamentarian stripped it from the budget reconciliation bill over the weekend because its inclusion violated the chamber’s rules. Lee is set to unveil changes to address the concern of hunters this week and may also tweak the proposal to get it back into the reconciliation bill. Even if that isn’t successful, standalone legislation is possible.

Folks, this is an opportunity to begin pulling our society back from the brink. As billionaires liquidate the federal government and the MAGA cult comes for our rights, we have a chance to build bipartisan agreement that our land and our rural heritage is core to our society and not for sale. We can build an alliance to draw a line in the sand.

Republican state legislators in New Mexico who represent areas that include public lands — like House Minority Caucus Chair Rebecca Dow of Truth or Consequences and Sen. Crystal Brantley of Elephant Butte — would be great allies if we could convince them to oppose Lee’s public land selloff.

Both represent the area I described at the start of this column where my dad and I hunted oryx. I’d love see them defend the public’s ownership of and access to that land. I’d encourage you to reach out to them and other prominent Republicans in our state.

A glimpse at the past

Another good Republican to contact is House Minority Leader Gail Armstrong, whose district includes the tiny town of Kingston in the Black Range on the east end of the Gila National Forest.

Kingston is surrounded by public land. I’ve written about this area many times before, and I own land in the area.

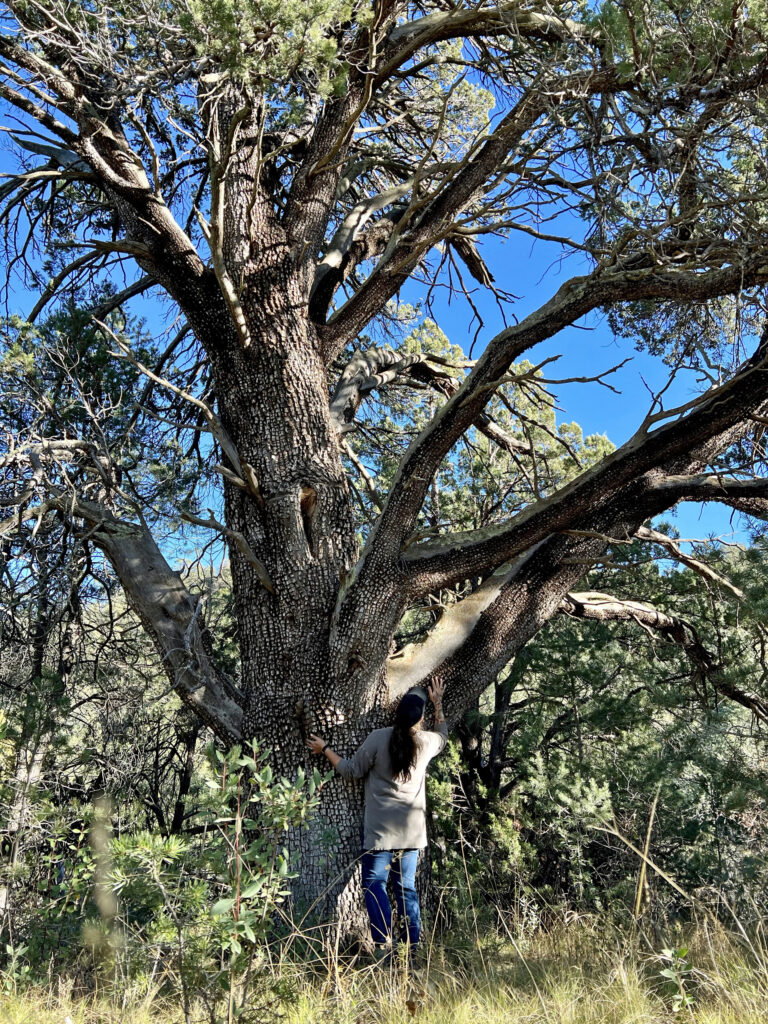

There’s a spring near the town that’s surrounded by fencing to keep cattle out. Alligator junipers tower above water that leaks out of the ground and runs gently into a wash that becomes a creek. The grass is several feet tall. Wild roses, reeds and other lush plants grow along the water.

There aren’t many places like this left. Wandering there offers a glimpse at the past, before cattle grazing destroyed springs and the habitats they birthed across the West.

This spring is on Lee’s list of land that should be considered for sale. All the public land surrounding Kingston is on his list, including the popular Emory Pass picnic and lookout area and much of the trail from that pass to Hillsboro Peak.

Selling off that land could make the peak and that portion of the Aldo Leopold Wilderness inaccessible.

Preserving our history

In the late 19th Century, Kingston was a booming mining town. Today it is home to only a few dozen people. They are folks who love the outdoors, who toil in these rugged mountains, who help preserve the history of the town and the surrounding area — the history of the American West.

There’s a cemetery just outside town. It’s on land Lee would consider selling. It’s owned by the Forest Service and maintained by folks in Kingston. The first people were buried there in the 1880s. People are still buried there today. Imagine the history, the connection to community, that could be lost if it’s sold.

The Trump Administration puts a price on everything. Nothing is sacred, even if it’s finite. Trump makes decisions based on what benefits him, not the people he was elected to represent.

Billionaires have been increasingly buying up land across the West. Many are foreigners. They’re all accustomed to Trump being willing to deal if they dangle something he wants.

Maybe they want the hills above Kingston. They’d be great places to build bunkers to hide in while society collapses and climate change alters the planet.

Lee’s proposal could destroy Kingston and so many other small towns like it. It’s an assault on our nation’s rural way of life and our heritage.

New Mexico’s romantic attachment to its “rural way of life” & its strident anti-business mentality combine to force our college-educated & more intelligent high school grads to move out of state to find jobs that pay well. The “brain drain” is well-known as is the continuing loss of not only good jobs but the tax dollars & other ancillary benefits to the state that businesses provide. Already, there’s talk of raiding the permanent fund that depends on oil & gas production to pay for more public projects while also considering cutting back on that production.

The continuing back & forth in Santa Fe may be illustrative of the schizophrenic mindset of the state. The wealthy build fancy homes up in the foothills, then complain about “light pollution” from porch lights & street lights of the ordinary folk down in town, who complain, in turn, of the desecration of the foothills by the “californicators”. Who’s right? Who’s wrong? Or is anyone right? I sometimes wonder if Earth doesn’t think of us humans the same way we’d think of a fungus!

Any monies from the sale of public lands could certainly POTENTIALLY be put to good use in a poor state like ours—has anyone considered that?

Thanks for your comment, Karen. While I don’t agree that our rural way of life forces college grads out of state, I appreciate your thoughts. And clearly New Mexico does need to do some things different. I think it’s begun doing that in recent times by developing a more active outdoor economy that brings in tourists who visit and support our small businesses. That creates the opportunity for college grads to create businesses and jobs in the places they were raised. Las Cruces has seen economic growth because of the creation of the national monument. Our public land is one of the resources we have to offer. Because of the need to diversify our economy beyond oil and gas, I wouldn’t want to sell off land that contributes to another source of revenue for local and state governments, businesses, and people.

An outdoor economy won’t replace oil and gas by itself, but it’s a good contributor to an overall plan.

In addition, our fossil-fuel-burning way of life is harming the planet and destroying ecosystems. If anything we need to rest more of our land, not sell it for profit.