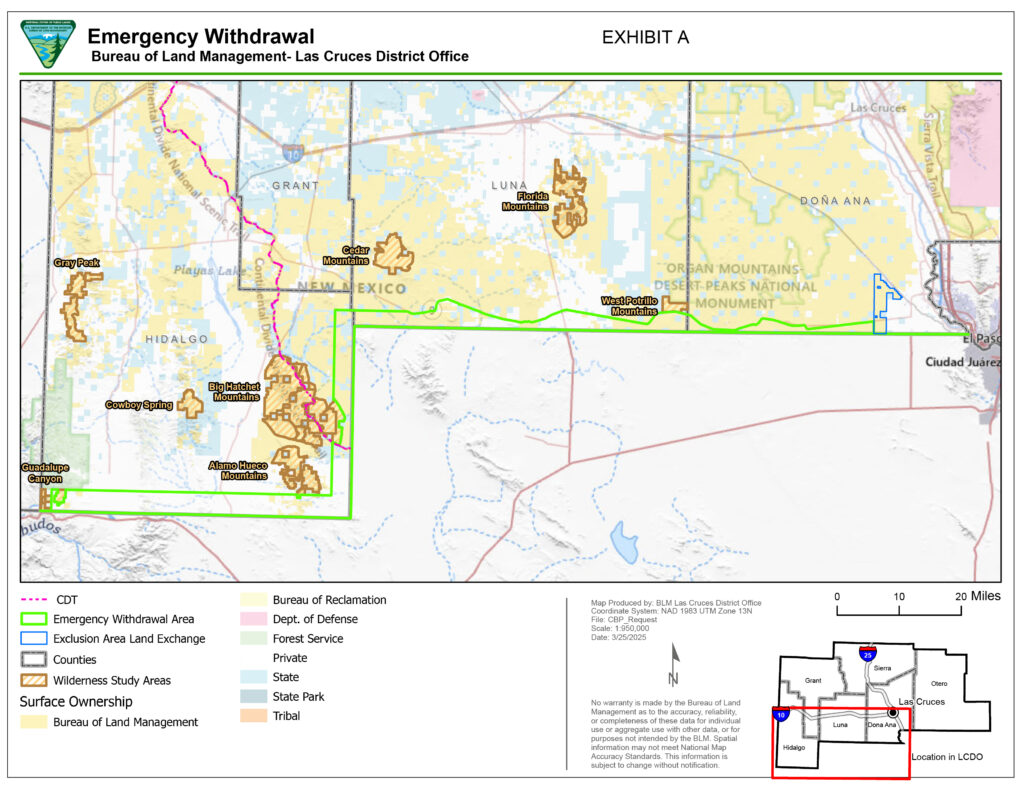

The new U.S. Army base that spans New Mexico’s entire border with Mexico isn’t just a 60-foot-wide buffer zone where soldiers can detain immigrants who cross illegally, in spite of what’s being promoted.

It actually cuts as much as 3.5 miles into New Mexico in some areas, snagging vast swaths of public land and threatening to snare hunters, hikers and others.

There are no signs identifying the land as being a part of Fort Huachuca on the north side, where New Mexicans are most likely to enter it. There’s only a barbed wire fence to keep cattle off the road. There are openings in the fence and roads that ranchers, hunters and others have used to access the land in the past.

The Trump Administration says it won’t tolerate trespassing on the Army base. The acting U.S. attorney for New Mexico announced changes against 82 people last week — apparently all folks who entered the Army base from the south side, crossing the border from Mexico.

Acting U.S. attorney Ryan Ellison said the goal is to “gain 100% operational control of New Mexico’s 170-mile border with Mexico.”

“Trespassers into the National Defense Area will be Federally prosecuted — no exceptions,” Ellison said in a news release.

A federal court hearing in Las Cruces on Thursday was full of people facing new charges.

Just as the Trump Administration’s attempt to leave Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia to rot in El Salvador will erode due process rights for all of us, if successful, this harebrained idea to create a military base along the border so the Army can detain immigrants creates serious trouble for U.S. citizens and non-citizens alike.

In case there’s any doubt that this is the intent, check out the video Republican state Sen. Ant Thornton of Sandia Park posted on social media last week.

“I believe this is a brilliant solution to our state’s border crisis,” he said. “…This new national defense area buffer zone is now considered military property, and anyone caught in this area can be arrested on charges of unlawful entry of military property, including U.S. citizens.”

Frustrated that the U.S. Attorney’s Office, politicians like Thornton, and many news organizations are mischaracterizing the military base as only a 60-foot-deep buffer zone known as the Roosevelt Reservation, I went to the border on Saturday to see it for myself.

Stepping onto Fort Huachuca

You can see the border wall clearly as you drive south on Interstate 10 toward Sunland Park and El Paso. But what was most striking to me as I drove into Sunland Park on Saturday was the armored combat vehicle parked on a mesa above the Anapra neighborhood.

Anapra is one historic community that an international boundary cut in half. The first time I visited the border in this area, in 2012, there was just a fence between the United States and Mexico. I had a conversation with a boy on the other side.

Today the wall looks to me to be twice as tall. It stretches toward the horizon in both directions. Army soldiers watch the area from above.

I pulled over next to a few homes on Posey Road to photograph the U.S. Army Stryker on the mesa on Saturday. Gambel’s quail pecked at the dirt on both sides of the road in front of me. Two U.S. Border Patrol vehicles were parked ahead.

I approached them to ask about ground rules. I wanted to investigate, but I didn’t want to be detained by the Army. I was carrying my passport along with my Real ID-compliant driver’s license, just in case.

I identified myself as a journalist and a hunter. I told the Border Patrol agent I’d studied a map of the new Army base. People hunt deer and quail in the border region, I said. I shared my concern about the lack of signs on the north side of the military zone.

While the Border Patrol and Army were focused on immigrants coming from the south, I told the agent, I was worried that armed hunters, including U.S. citizens, would wander onto what’s now an Army base without realizing they were trespassing.

At Anapra, the military base is only 60 feet deep along the wall. That’s where the Army and Border Patrol stage media events, which may be why so many journalists have missed how much land the Army has swallowed.

The Border Patrol agent told me I could walk up to the wall at the end of Anapra Road even though I’d be stepping foot onto Fort Huachuca. I told him I was going to drive west along the border as well. He let me know Army soldiers were out there putting up signs warning people against trespassing.

After a pause he said, “but only from the south,” acknowledging my point about the north side of the land. He said he wasn’t even sure where the Army base’s north boundary was located. He’d just been told to cover the whole area.

The agent told me he would let others know I was out there so no one would bother me.

I thanked him and went to see the wall. I stood in the spot where I’d talked to the boy years earlier. I felt sad. I can remember a time when we almost reformed our broken immigration system, when it felt like we might put our nativism aside and demilitarize.

An Army Stryker above a school

There are two elementary schools located only a few hundred yards from the border wall in Sunland Park, a city of almost 18,000 residents.

Sunland Park Elementary is surrounded by homes on three sides. To the south is a rail line, the mesa, and then the border wall.

The Stryker is ominous above the neighborhood. Imagine U.S. Army soldiers perched on a high point above your home, watching everything around them with binoculars. Imagine them watching your child’s elementary school.

That’s what’s happening in Sunland Park.

Motorists slowed and looked at me while I photographed the Stryker on the hill above the school. I wondered about their lives. What is it like to be watched this intensely by your government?

Maybe it’s naive to think we all aren’t being surveilled like this. Maybe it’s just more obvious in Sunland Park.

I got the photo. Then I drove west.

An unmarked Army base

Santa Teresa is home to an industrial park the State of New Mexico has been building for decades. There’s a border crossing, a Union Pacific rail hub and an airport run by Doña Ana County.

There’s also a U.S. Border Patrol station. A blimp is tethered to the ground and keeping an eye on the border from above. The station is located on Highway 9, which runs west from Santa Teresa to the next port of entry at Columbus in Luna County. The road continues from there to Rodeo in Hidalgo County.

Through Doña Ana and Luna counties, Highway 9 is the north boundary of what is now Fort Huachuca.

The desert is so dry after years without a significant monsoon season. It was sunny and warm on Saturday. There were a few other travelers on Highway 9, some with New Mexico or Texas license plates, others with Chihuahua plates.

There’s a point along Highway 9 where the military zone’s boundary takes a sharp turn north from the 60-foot stretch along the border wall and connects with the highway. I used an app on my phone that shows land ownership to find the spot. I pulled onto the shoulder of the road when I arrived.

The military base is almost two miles deep in that spot — far enough that even though the land is relatively flat I couldn’t see the wall in the distance. As expected, I didn’t find any signs warning folks to stay off military land. There’s just the barbed-wire fence to keep cattle off the highway. I took some photos and drove on.

Pretty soon I found a dirt road that crosses a cattle guard and heads south into the military zone. There’s some ranching infrastructure down that road. A turkey vulture sat on a fence post until I got out of my truck. Then it flew away.

I stayed off the Army base, so I wasn’t able to get a good look at the ranching infrastructure. I’m not sure if there’s water that would attract quail, but the spot confirmed my fear: An open road onto an Army base with no signs warning people against trespassing.

It reminded me of the statement I received from the American Civil Liberties Union of New Mexico. “We don’t want militarized zones where border residents — including U.S. citizens — face potential prosecution simply for being in the wrong place,” said Rebecca Sheff, senior staff attorney.

The road is certainly one hunters have used to scout for quail. I’m a hunter. We tend to be creatures of habit. We return to the same places year after year once we learn where the animals we’re seeking find sustenance.

State response

Last week, before I set off on my border trip, I called the state’s Department of Game and Fish to ask about my concern for hunters. The agency’s communications director, Darren Vaughan, asked me to email him questions. I sent him an article about the situation, a map of the military boundary, and some questions.

On Friday, he sent a response: “The Department is working with BLM and DOI. We are tracking the progress and working to ensure hunters have access.”

That raised more questions for me. What do the Interior Department and Bureau of Land Management have to do with this? It’s not BLM land anymore; it’s Army land, at least for the next three years. And was Vaughan saying Game and Fish is optimistic hunters will be able to safely hunt on this land even while it’s in Army hands?

I emailed back. I’ve received no response.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for the state’s Department of Justice told me that agency is “closely monitoring the situation.” That’s more than I got from the Governor’s Office, which didn’t respond to several requests for comment.

A few weeks ago, when news first broke that Trump might create a military zone in New Mexico, a spokesperson said the Governor’s Office was “closely monitoring the situation at the border and weighing our options, including challenging actions in court if and when appropriate.”

U.S. Rep. Gabe Vasquez, D-N.M., who represents this area, has hunted along the border before. He understands my concern. He pointed to the border region as a place where New Mexicans enjoy public lands and explore our history and culture.

“Taking away the opportunities to enjoy our public lands is a threat to all of us,” Vasquez told me. “There are better, more effective and efficient ways to manage security threats at our border.”

Hunters and travelers

I’ve never hunted along the border, but I treated Saturday’s drive as a scouting trip. I looked to hills to the north — particularly the Potrillo Mountains, which are not part of Fort Huachuca — as a place where a buck might be hiding.

I saw many spots where I’d look for quail in the fall, especially if there’s a decent monsoon season — arroyos where trees and shrubs are growing, low-lying areas where grass sprouts after it rains, places that are now on an Army base.

While I drove west, the land between Highway 9 and the border wall narrowed. Eventually I was able to see the wall to my left. I pulled over to photograph a house on the other side of the international line.

I stared at the house through binoculars, too. I wondered what life is like there. I lamented the human tendency to put up walls that interrupt curiosity and block understanding.

On my last stop before I turned back, I was on the shoulder of Highway 9 in far west Doña Ana County, only 500 yards from the border wall. A dirt road headed south through Army land toward the wall, and next to it was a massive pile of metal and concrete. The federal government is storing materials here to build additional sections of the wall.

Once again, the road was open and there weren’t any signs.

I took some photographs. I sat on my truck’s tailgate for awhile and ate a sandwich on the shoulder of the road — in the state Department of Transportation’s easement, not on Army land. I watched occasional vehicles pass.

I wondered how many folks think about pulling over at this spot to have a look at the wall and the construction materials.

Other than the Stryker in Sunland Park, almost 35 miles to the east of the pile of wall materials, I didn’t see evidence of the Army on my drive. But there were big stretches where I could not see the wall.

I don’t doubt what the Border Patrol agent told me, that soldiers were out on Saturday putting up signs facing south along the wall. I drove along the border through most of Doña Ana County but didn’t get to Luna or Hidalgo counties.

I wonder what will happen when the Army eventually encounters a U.S. citizen who stops on the side of the road to pee or wanders down one of the arroyos with a shotgun, dressed in camouflage and looking for quail.

I wonder what will happen if that person is brown and has some tattoos.

Maybe it has already happened. Maybe they aren’t telling us.

This is an important article. Keep up your work. This is serious business. There is no excuse for State officials, elected or otherwise, not to be actively aware of what is going on and to ensure that all people are protected from inappropriate and even dangerous behavior by the U.S. military or federal, State, and local law enforcement personnel. Unfortunately, we are not far from the realities of a “police state.”

Thanks for your kind comments. I’ll keep doing my best!

The only question is what brown kid be be the next Ezequiel Hernandez? What family will be denied justice when they lose a child to this political theater?