There’s a spring in the Black Range in Sierra County that’s surrounded by fencing to keep cattle out. Wandering there offers a glimpse at the past, before cattle grazing destroyed springs and the habitats they birthed across the West.

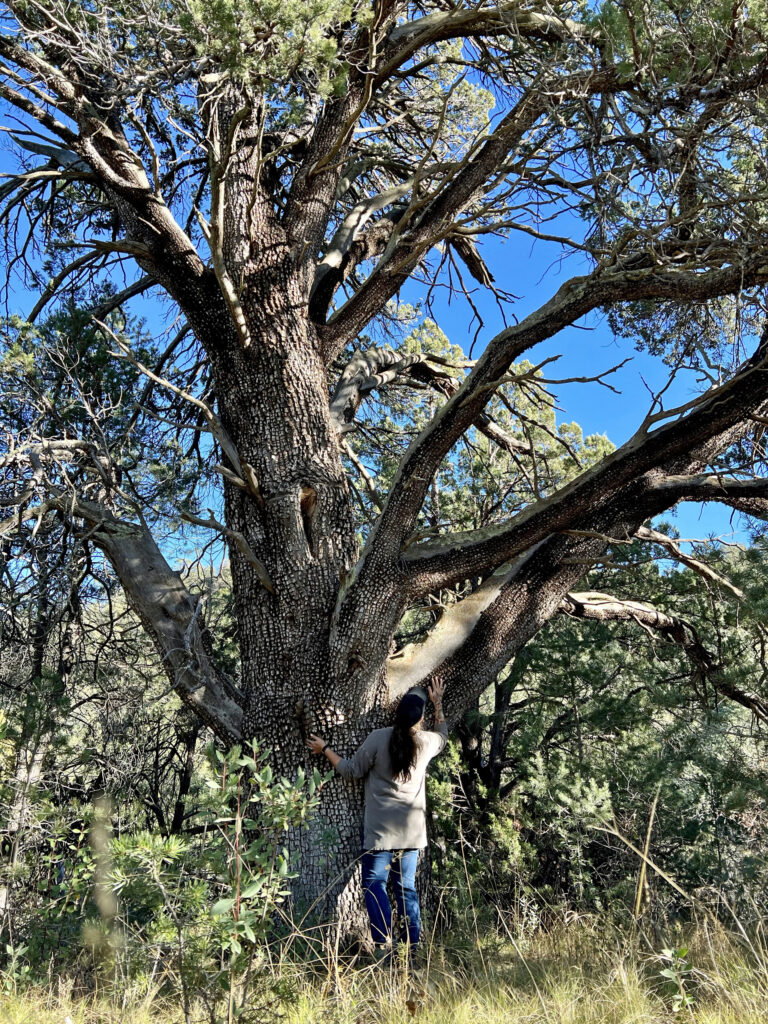

Alligator junipers tower above water that leaks out of the ground and runs gently into a wash that becomes a creek. The grass is several feet tall. Wild roses, reeds and other lush plants grow along the water. I found a Missouri Evening Primrose blooming there last summer.

A pipe runs from a hole drilled through rock near the water to a trough on the other side of the fence. That’s where the cattle drink.

There weren’t cows in the pasture around the spring in 2024. It was a designated rest year for the land. But the effects of the previous year’s grazing were still visible.

There was a literal pile of shit around the trough. It slowly decomposed into the ground through the summer and fall next to the creek. The plant life around the trough and downstream was pitiful compared to what grew inside the fence.

It was a similar situation on land my spouse Sarah and I own nearby that borders the national forest. On our side of the fence, lots of grass. On the other side, mostly dirt.

Lots of destruction for little food

With the exception of a few spots like the protected spring, public lands across the Western United States are similarly decimated to feed and water some cows.

The United States produces about 20 percent of the world’s beef, according to the USDA. Most cattle aren’t grazing on land the taxpayers own. One study says less than 1.6 percent of the forage eaten by cattle in the United States comes from public land. In exchange for that little bit of food, domestic livestock are grazing 85 percent of all public lands in the West, the study found.

That same study, conducted by four researchers from Oregon, found that those cattle make “profound” contributions to climate change through digesting the food they eat, which produces greenhouse gases; by destroying native habitats, which shifts land from storing carbon to becoming yet another source of emissions; and by contributing to “warmer and drier conditions.”

In addition to the environmental impact, in many instances grazing isn’t sustainable for the ranchers who are trying to make a living. I spoke with one in October while oryx hunting near White Sands Missile Range who supplements his livestocks’ diet with feed he hauls in. With less grass growing and extreme storms battering the green that does grow, he wondered aloud how long he would be able to keep ranching.

If the government compensated them for the infrastructure and work they’ve put into the land, I suspect some ranchers would jump at the chance to get out of the business and let the land rest.

The grass can grow back, but it has to be given time to do that — and in our forests and deserts, that usually isn’t happening. A season of rest isn’t nearly enough. Erosion caused in large part by decades upon decades of grazing has washed and blown away much of the topsoil that would have nurtured new grass. And because the West is experiencing aridification caused by climate change, the water that would help regrow grass simply isn’t here.

Healing the land

In spite of those challenges, healing the land is possible when you eliminate cattle.

Sarah and I have been working since we bought our land in 2020 to heal an old road scar and two arroyos — one of them a deep, unnatural cut in the land. We’ve built dams with rocks and branches to slow the flow of water. We’ve chipped dead wood and spread that organic material to help improve the soil with the help of a grant from the N.M. Department of Agriculture’s Healthy Soil Program. We’ve spread grass seed each of the past three years. In that short time, it’s made such a difference.

The deer have noticed the tall grass. In 2023 and 2024, does gave birth to fawns on our land, where there’s cover from predators. It’s been so much fun watching the babies on our trail cameras. Twin fawns have grown up among that grass, and I got to see them in real life when I spent time up there last summer.

The does attract bucks. During mating season last year, eight distinct bucks appeared on our cameras. That’s a lot.

A covey of Gambel’s quail makes its home on our land. A roadrunner appeared for the first time last year and has stuck around. While I was up there last summer, I heard it calling almost every day.

A healthy population of deer and javelina attracts predators. We see coyotes, bobcats, grey foxes and a mountain lion on our cameras. Last fall a mountain lion killed a doe. The skeleton still lies near the tree where the deer was bedded down when it was ambushed.

It all starts with grass.

Why keep doing this?

The grass helps hold the soil in place. A ravine that runs through our land has been eroding for a long time — probably since the 1880s, when the nearby town was built. A trunk from what was once a giant alligator juniper, which has still not fully decomposed, sits at the start of the wash. It reveals the likely moment when humans started causing damage. People began grazing livestock here around the same time.

There are deep, ugly cuts in the land. Water rushes through them during heavy rains, digging even deeper, pushing soil into a creek that will carry it to the Rio Grande and beyond.

If you sit quietly and look long enough, you can picture the long-lost valleys these ravines have replaced. Water probably flowed slowly through them, with grass and other plant life holding the soil in place and sucking up much of the water.

Climate change, which is caused by many human activities beyond livestock grazing, is a significant factor in how these landscapes are transforming. Forest mismanagement is, too. Both have led to the most massive wildfires imaginable.

But livestock grazing has been contributing to this problem since long before we adopted our misguided, century-long policy of suppressing all fire, and also since long before we significantly altered the atmosphere.

I hiked quite a bit while I was in the Black Range last summer. One day I set out for a different spring that appears on my map, one I’d never seen. I discovered an old trail and ended up on a ridge with views in all directions. Cow patties from 2023’s grazing littered the ridge. Their presence among the flowering prickly pear cactuses felt jarring.

As I headed downhill toward the spring, I passed a bear den. Then I found the water.

That spring is unfenced and trampled. The water runs from a pipe into a giant, old tire. The land around it is barren. It’s exactly the type of landscape researchers who conducted the study from Oregon were describing.

Almost none of the beef that’s sold in grocery stores comes from cows who were substantially sustained by the forage that grows on public lands. The benefit doesn’t come close to mitigating the costs.

Why are we still doing this?

What’s possible

I took my daughter to the fenced-in spring in mid 2024. I wanted her to see what’s possible when we take care of the land. We sat at the water for awhile, then wandered around thickets back to the gate.

We were stepping over a mud bog and ducking under tree branches when a female turkey jumped up from a hiding spot among the bushes and hurried away from us. Hens usually lay eggs near water, and it was the right time of year for her to be sitting on a nest. We didn’t search any further; I didn’t want to disturb her more than we already had.

Climate change is killing the ponderosa pines in these mountains that provide safe perches for turkeys to sleep on at night, and their habitat is shrinking. But this spring — this wild, vibrant, healthy space — gives life to the ponderosas around it and provides water for the hen whose babies would soon be wandering these hills with her, as I was wandering them with my daughter that day.

Heath, thank you for posting this! It has become a top issue for my friends and family who live in and explore public lands. We breathe and drink the devastating results of cattle grazing.

Top issue for me too!

Excellent informative article

Thanks!

As climate change drives aridification I’d like to know more about what is happening to the industry. The dust storms are pretty clear indications of the condition of the land. Of course the federal agencies won’t be able to publish any research for the next four years.