It’s not easy for many elected officials to admit a mistake. That’s especially true when they’ve broken the public trust with a string of wrong choices that illegally excluded the people from the people’s business.

And yet, every member of the Las Cruces City Council did the hard thing on Monday. During a nearly three-hour slog of a meeting, they all owned up to mistakes they made while hiring a new city manager last year. Three of them apologized.

Some also complained about it, but even that was part of what appeared to me to be an honest attempt to grapple with their own failures and right a wrong.

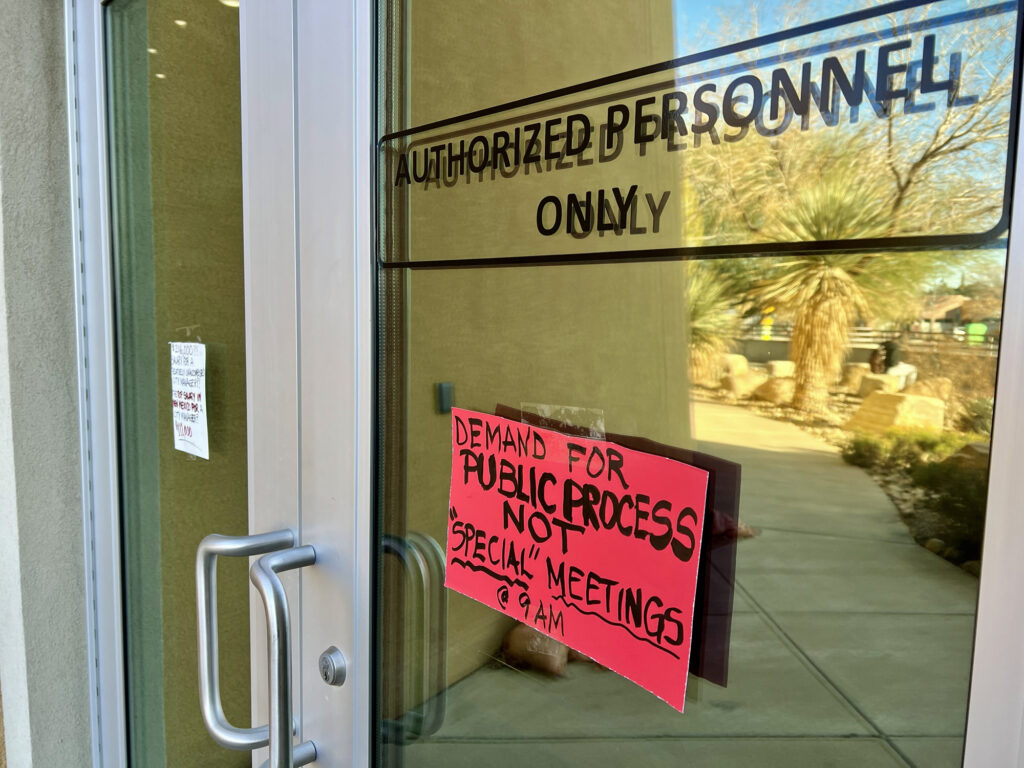

Many folks will not be satisfied with the resolution. New Mexico allows governing bodies two choices when they violate the Open Meetings Act (OMA). They can redo in public the thing they illegally did in secret. In this case that would have meant starting the search for a city manager over.

Or they can hold a new meeting to detail what they did for the record and then re-vote, essentially affirming in public the thing they did in secret. This is the option the Council chose. It meant detailing every step in the process they undertook behind closed doors to hire a new city manager about 10 months ago and taking several votes that amounted to ratifying the hiring of Ikani Taumoepeau.

That option absolves them legally, but it doesn’t change the fact that something is permanently lost: A process that could have involved the public in a critical decision was instead a rush job that included very little public notification and no input from city residents and others.

In this instance, the opportunity to co-create with the public is gone forever.

Skepticism and scrutiny

Councilors voiced nothing but approval on Monday for Taumoepeau, who was not present at the meeting. They expressed no desire to start over, even if it would give them the chance to model a partnership in making such decisions with the folks who put them in office.

An understandable choice, perhaps, but one that leaves them at a deficit in terms of public trust.

That is, ultimately, the consequence of so egregiously violating a law that states that “a representative government is dependent upon an informed electorate.” It’s the policy of the state, made explicit in OMA, that “all persons are entitled to the greatest possible information regarding the affairs of government and the official acts of those officers and employees who represent them.”

New Mexico law requires public policymaking bodies like city councils to involve the people they serve in their discussions and actions. The Las Cruces City Council fell spectacularly short of that requirement when it hired Taumoepeau last year.

“The City Council’s opaque process deprived the public of any opportunity to meaningfully participate in the selection of a new city manager,” Blaine Moffatt, director of the N.M. Department of Justice’s government counsel and accountability division, wrote in a letter to the city in December. “As a consequence of these violations, the city manager selection is invalid.”

That letter, which followed a nine-month investigation, was one of the harshest determination letters I’ve ever seen the DOJ issue to a local government. “Future complaints related to your public body will be examined with increased attention,” Moffatt wrote.

As a result of the choices these elected officials made, public skepticism and additional scrutiny from the DOJ is their reality for the time being.

‘Can we do better? Absolutely.’

It didn’t have to be this way. The Open Meetings Act is really not that complicated. As long as you’re erring on the side of including people in the process, instead of excluding them, you’ll usually end up on the right side of the law. The fact that most councilors and the mayor didn’t reveals how severely they had lost touch with the people they were elected to represent.

I’ve seen many situations like this during my career as a journalist. So I spotted the violation immediately when the city announced in a Feb. 28 news release that it was accepting internal applications for city manager even though councilors had not yet discussed the issue publicly. I twice emailed Mayor Eric Enriquez and Councilor Yvonne Flores — who I erroneously thought at the time was my councilor — to detail the ways in which they were breaking the law and give them guidance on how to fix the situation before it was too late.

I wanted to help them avoid creating unnecessary scandal and stop eroding public trust in the city.

Flores, who had responded to my emails in the past, before redistricting moved me out of her district, did not respond to these emails. I thought about that on Monday when she said, “whoever felt that it was inappropriate to hold this meeting should have raised it before it was held.”

The mayor phoned me last year after I sent those emails. He listened to my concerns and called me a subject-matter expert on transparency laws.

Then he told me why I was wrong.

Of course, it was Enriquez who was wrong. In spite of the N.M. Foundation for Open Government warning that their process violated state law, the city doubled down on its rushed course of action and took its final, illegal vote to approve Taumoepeau’s employment contract on April 1.

On Monday, Enriquez went through the motions to correct the violations but did not apologize. He promised to be better.

“I do want to cure and ratify this process,” he said. “…Can we learn from it? Absolutely. Can we do better? Absolutely.”

He wasn’t as clear at a meeting a week ago, when the Council delayed correcting its violations to take time to get clarity from the DOJ about how to do that. After that meeting, Enriquez was quoted by the Las Cruces Bulletin as taking issue with parts of the DOJ’s report, saying he did not feel some of the “evidence was correct.” He was quoted as saying some alleged violations were more like “inferences.” He did say it was “fair” to “ratify” the city manager hiring process.

Apologies and promises

Every city councilor did a better job than the mayor of engaging in genuine discussion in front of the public on Monday and wrestling with correcting the violations. Best, not surprisingly, was Councilor Cassie McClure, who was only weeks into her tenure on the Council when it hired Taumoepeau last year. She cast the lone vote against approving his employment agreement in March. That was her way of protesting the process.

“I apologize to the public,” McClure said on Monday. “…I do very much value transparency. … I hope to do better.”

Councilor Bill Mattiace, a former mayor, also apologized. “I hope to do better as well,” he said.

The other apology came from Councilor Johana Bencomo, the mayor pro tem. She apologized to the public, and also to the three city manager finalists the Council named last year before picking Taumoepeau, “for having made decisions that put you in this situation nine months later.”

Councilor Becki Graham called the job “a constant on-your-feet process” and said this situation “has certainly driven home to me not just the importance of transparency but the importance of the public perception of transparency.”

Councilor Becky Corran agreed. “The big picture is we could have done better, we will do better, and that’s what we’re committing to. That’s what I’m committing to,” she said.

Flores said she didn’t understand what the violations were, but she also committed to trying to be better. “It doesn’t feel good to be up here and have tomatoes thrown at us,” she said, adding, “If there’s anybody out there in District 6, please take my place. I’d be very happy to relinquish it.”

Building a stronger democracy

I know many folks will find the legal remedy councilors chose unsatisfying. A small but forceful group of citizens urged the Council on Monday to conduct a new search for a city manager instead of ratifying Taumoepeau’s hiring.

It’s important for elected officials to remember that public mistrust in government is sky high. Failures like the Council’s do immense damage to public perception of government. Healing rifts takes time.

We’re on the road to fascism right now. Flores urged people who are holding the Council accountable to apply the same level of scrutiny to the incoming administration of U.S. President Donald Trump. That’s not only fair, it’s critical. The Trump administration is the biggest threat to our democracy since at least the Civil War.

But the public interacts with government the most at the local level. This is where decisions are made about the condition of our roads, the wages we’re paid, and funding for our kids’ classrooms. These are the folks who have to grapple with our unhoused and crime problems. These are the people we run into at the grocery store.

And so these elected officials are on the front lines in the fight to build trust in government. They do immense damage when they fall short, regardless of their intent.

It is critical that local officials involve the public in their decision-making processes — not only because the law requires it, but because they make better decisions when they build something together with their constituents. They also help create a more active, informed electorate and a stronger democracy. This is one critical way we can combat our society’s descent into fascism.

With the city manager mess now behind them, councilors and the mayor have a second chance. And people have an opportunity to watch their elected officials closely to ensure they keep their promises to be better.

If they don’t, voters can hold them accountable the next time they’re on the ballot.